The Investor September 2017

A bright future lies ahead

by Richard Cluver

There is, wherever I go in South Africa today, a sense of deep gloom born out of extreme frustration which has left so many of us feeling impotent and confused about what we should be doing to ensure our future well-being.

It is the understandable result of a perceived collapse of the established order of things. A recognition that bad people are getting away with things; that a few connected families have gained control of the purse strings of the nation and are stealing us blind, and because their henchmen and appointees now head the normal regulatory systems of the country, there is no retribution. Thus we have witnessed a breakdown of the accustomed processes of law and order that are the glue that holds our society together.

Furthermore we have witnessed the ability of the bad people to harness previously respected bastions of the civilised way of doing things, a top international auditing company and one of the world’s largest public relations partnerships which have between them been paving the way for even worse things to come. In the old fashioned sense of the political system, the peasantry are being roused to invade productive farm lands, murder farmers in their beds and storm onto city construction sites to intimidate workers in a bid to capture swathes of profitability…and nobody in authority seems to care.

Worse, having stolen practically everything there is to steal and running out of fresh caches of wealth with which to pay off this ever-growing Ponzi scheme of nominal supporters that enable them to hang onto power, they have in desperation ignited that last resort of failing despots, a chant that daily grows in strength, that their enemies are their private sector employers. It is the classic ploy that if you can divert mob anger to pause and tear down the very structures that feed them, you can quietly slip away to Dubai or some other distant oasis before you who initiated it all get your just desserts.

What we tend to forget in all of this is the indignation of the good people and the widely understood truism that when good people do nothing, evil will flourish. The leadership of the ANC is acutely aware that with every day that passes their chances of being re-elected in the next general election, which at the very latest must take place within the next 18 or so months, are rapidly fading away. Career politicians who recognise that they have little chance of gaining meaningful employment outside of Parliament, the Provincial Councils and municipalities, are similarly aware that every day Jacob Zuma and his cronies remain in power increases the probability that they will soon be out in the cold. So, it is no wonder that ANC branches are so deeply divided that the probability of their being able to hold a successful electoral conference in less than three months time is becoming increasingly unlikely. They can barely talk to one another let alone find points of agreement and must accordingly resort to the courts to score political points against one another.

This is not an organisation that can stage an elective conference in less than three months time, let alone organise itself with any hope of winning a national election.

Right down to the ANC ranks, its members are now deeply aware that, if the party is to survive beyond the 2019 polls it will need to rid itself of everyone who is remotely tainted by corruption and state capture. But since, in the minds of so many of our people a career in politics and instant access to the seemingly endless financial resources of the State are effectively synonymous, this is a nearly impossible task, certainly within the short time frame that remains before the next election rolls around. Thus, in the view of most analysts, it is now becoming a given that the ANC will LOSE the election.

All of which brings me to the big question: is it possible that with the right people in power South Africa’s economic direction can be turned around?

There is the pessimistic view favoured by President Zuma when confronted with evidence of South Africa’s rising rate of unemployment and collapsed GDP growth figures, that a return to our previous era of prosperity is impossible because of global recessionary conditions. And it is indeed true that the Developing World is undergoing foreign trade difficulties largely due to the fact that the Developed World no longer needs our raw materials in the same quantities as previously. But that is only half the story.

There is the pessimistic view favoured by President Zuma when confronted with evidence of South Africa’s rising rate of unemployment and collapsed GDP growth figures, that a return to our previous era of prosperity is impossible because of global recessionary conditions. And it is indeed true that the Developing World is undergoing foreign trade difficulties largely due to the fact that the Developed World no longer needs our raw materials in the same quantities as previously. But that is only half the story.

The reality is that the majority of South Africa’s employers have long ago learned to live with the recession. They are lean and streamlined and their war chests are stuffed with cash that would enable them to almost instantly move into overdrive were they offered a stable economic climate within which to operate. All they ask for is the removal of policy uncertainty and evidence of Government commitment to a realistic economic development plan. But such has been their experience of ANC government that they are pessimistic about ever seeing such things from the present party. Accordingly, most large companies have become outward-looking, seeking their profitability and growth elsewhere in the world and their most highly skilled and capable manpower is currently directed towards managing assets in Europe, the Far East and, indeed, everywhere but in South Africa.

It is thus likely that for South Africa to get up and running as an efficient profit machine that could deliver the hope of rising employment rates and, accordingly, political stability, we need a new political party in charge with a clearly laid out re-development plan. It is not a particularly difficult thing to do. For example, it has under the current administration become nearly impossible to fire an underperforming employee. So employers look twice, thrice, and then again another time before they consider taking on someone new, preferably resorting to costly mechanisation solutions instead. So if you want to deal with unemployment just make it easier for employers to rid themselves of unproductive workers.

Then, our mining industry was once a world leader in technology and the country’s largest employer, but it has been in steady decline throughout the tenure of the ANC. Yet we have many of the world’s richest and most easily-mined mineral deposits. The ANC’s solution to this was to introduce a series of mining charters that have brought the industry to its knees. All the miners ask for is a policy framework which ensures some sense of stability into the future and one might reasonably expect to see a new mining renaissance in this country just at the time when mineral prices have begun a steady improvement once more.

I could go on with a series of similar examples, but I believe I have made my point. However, there is one major point to highlight because few people really realise how corruption can paralyse a country.

Consider for a moment that businesses as fundamental to a country as grocery stores are “safe” businesses to be in because come rain or shine, boom or depression, people always need food. Because of this guarantee, grocers can operate at a low profit margin. To quote the publication Supermarket & Retailer: “Shoprite has led the market consistently for the last 10 years, with its trading profit margin rising just about every year from 3% in 2005 to 5.6% in 2014”

Other industries need higher margins to enable them to survive through our economic cycles, but hopefully you get the point that businesses and nations operate on very slender profit margins. If you start stealing from the till, it wont be long before the average business is bankrupted. Now consider that economists calculate that upwards of 10 percent of South Africa’s revenue is being lost to corruption and you can easily see why SA Pty Ltd is in negative growth right now. End corruption and you have a fighting chance that our economy will boom once more…and with economic prosperity comes social harmony within which education can flourish and we can all look forward to a brighter future.

Of course I have simplified things somewhat, but hopefully you get the picture. It is in your hands and mine to change the trajectory of this country from gloom and doom to hope. If you do nothing else, make sure you use your voting power to ensure change and make sure everyone you know appreciates what needs to be done. Then we might be able to look forward to a time when the average family does not include at least one emigrant child!

What the dollar means for the SA economy

by Brian Kantor

The most important single indicator for the future direction of the SA economy is the value of the US dollar compared to the euro and other developed market currencies.

When measured this way, and helpfully for SA and the emerging market world, we see that the US dollar has lost nearly 4% of its exchange value this quarter. Dollar weakness has brought a small degree of strength to emerging market (EM) currencies, including the rand, and to metal prices that make up the bulk of SA’s exports.

Dollar strength put pressure on the rand and EM exchange rates for much of the period between 2011 and mid-2016. This was when something of a turning point in dollar strength, weakness in metal prices (in US dollars) and rand and EM exchange rate weakness, was reached. Over this period, the US dollar gained as much as 30% against its peers, while the EM currency index lost about the same against the US dollar, while industrial metal prices and the trade weighted rand fell to about half their values of early 2011 in 2016. (See below)

The dollar has weakened and industrial metal prices have improved since 2016 because the rest of the industrial and emerging market world has begun to play catch up with the revival of the US economy. A stronger Europe and Japan imply more competitive interest rates and returns outside the US and hence less demand for dollars and more for the competing currencies and for metals.

The rand and dollar-denominated RSA bonds have benefited from these trends – despite it should be emphasised – less certainty about the future direction of SA politics and economic policy and a weaker rating accorded by the credit rating agencies. The rand exchange rate since lost more than 50% of its average trade weighted exchange value between 2011 and early 2016. The cost of insuring five-year US dollar-denominated RSA debt had soared to nearly 4% more than the return offered by a five year US Treasury Bond by early 2016. (See below)

Today this risk spread has declined to less than 1.8%, while the rand since early 2016 has gained about 15% on a trade weighted basis and 17% against the US dollar. This improvement has, as indicated, come with general dollar weakness and EM exchange rate strength. But it has also been strong despite the continued uncertainty about the direction of SA politics. The markets, if not the rating agencies, appear to be betting on a better set of policies to come.

It is to be hoped that the markets are right about this. The recent strength of the rand and metal prices offers monetary policy its opportunity to do what it can to help the economy – by aggressively reducing interest rates. Inflation has come down and will stay down if the rand maintains its improved value – and the harvests are normal ones – and the dollar remains where it is. Lower interest rates will lift spending, growth rates and government revenues.

Interest rates were raised after 2014 as the rand weakened and inflation picked up, influenced also by a drought that drove food prices higher. These higher interest rates and prices further depressed spending by South African households and firms and GDP growth. Consistently, interest rates could and should now be lowered because the rand has strengthened and the outlook for inflation accordingly has improved. Does it make good sense for interest rates in SA to take their cue from an exchange rate and other supply-side shocks that drive inflation higher or lower but over which interest rates or the Reserve Bank have no predictable influence? Their only predictable influence seems to be to further depress spending and growth rates. 15 September 2017

Cumulative trade balance to have remained in surplus in the first eight months of the year

By Kamilla Kaplan, Investec Group economics

The magnitude of the trade surplus is forecast to have narrowed to R2.2bn in August from R9.0bn in July on seasonal considerations. In the month of August, month to month export growth is typically lower than import growth. However, on a cumulative basis export growth has outpaced import growth yielding a surplus of R36.6bn in the first seven months of the year compared to a deficit of R4.7bn in the same period last year.

The improvement of the trade position can be ascribed to a synchronised lift in global growth and trade from post crisis lows reached in 2016. This coupled with higher commodity prices has aided SA’s export performance. Concurrently, weak domestic consumption and investment demand have restricted import growth.

PPI inflation is forecast to have lifted to 3.9% y/y in August from 3.6% y/y in July, mainly on account of the fuel price component, which will reflect the impact of upward statistical base effects combined with some upward pressure stemming from the increases in the oil price in July and August. Consequently in August, petrol and diesel prices increased by 19 and 29 c/litre respectively or by 5.7% y/y and 2.8% y/y. The August PPI update should also confirm continued manufactured food price disinflation. Manufactured food price inflation peaked at 13.4% y/y in August 2016 and has steadily declined, to 3.3% y/y in July 2017 on the favourable maize supply outlook. As such the decreasing contribution from the food products, beverages and tobacco products category, which holds the largest weighting in the PPI basket at 33.7%, has been the main influencing factor on the broader moderation in PPI inflation so far this year.

Growth in private sector credit extension may have risen to 6.2% y/y in August from 5.7% y/y in July on a modest lift in corporate credit, whilst household credit growth is expected to have remained muted. Household credit extension remains negative in real terms on both demand and supply side factors. On the supply side, credit conditions remain tight whilst on the demand side, depressed consumer confidence and deleveraging have diminished the uptake of credit.

South Korea: The Wild Card in the Korean Crisis

By George Friedman

Editor, This Week in Geopolitics

Last May, I spoke at Mauldin Economics’ Strategic Investment Conference and made two points on the situation on the Korean Peninsula. I said that the United States and North Korea had entered into a major crisis and that the crisis would likely lead to war. The crisis ensued, but war has not broken out. As North Korea test-fired another missile that flew over Japan late last week, it’s time to review what happened and why the war hasn’t materialized.

North Korea had been working on developing nuclear weapons for years; this was nothing new. But the development that turned this into a crisis was that the North had passed a threshold. There was evidence that North Korea had developed warheads small enough to be fitted to a missile. There was also evidence that Pyongyang seemed to be moving toward a new missile that would be capable of striking the United States.

One of the United States’ top imperatives is to keep the homeland secure from foreign attacks of all sorts. The possibility of a nuclear attack towered over all other threats. Logically, North Korea would not want to fire an intercontinental ballistic missile and endure the inevitable retaliation that might annihilate the country. The problem for the United States was that it could not be certain that North Korea would follow this logic; the fact that it probably would was not good enough in this situation. Therefore, the US would try to destroy North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities just before they became operational. The problem, of course, was figuring out how close North Korea was to developing an operational weapon. The United States was therefore in an area of uncertainty.

“Likely” Isn’t Good Enough

The US had little to gain from a war with North Korea; it wanted only to destroy the North’s nuclear program. The war plan was complex, and though it was likely to succeed, “likely” is not a term you want to use in war. North Korea’s nuclear and missile facilities were scattered in numerous locations, and many were underground or in hardened sites. And the North Koreans had massed artillery along their southwestern border, within easy range of Seoul. In the event of an American attack on North Korean facilities, it was assumed those guns would open up, killing many South Koreans. Destroying those batteries would require a significant air campaign, and in the meantime, North Korean artillery would be firing at the South.

The US turned to China to negotiate a solution. The Chinese failed. In my view, the Chinese would not be terribly upset to see the US dragged into a war that would weaken Washington if it lost, and would cause massive casualties on all sides if it won. Leaving that question aside, the North Koreans felt they had to have nuclear weapons to deter American steps to destabilize Pyongyang. But the risk of an American attack, however difficult, had to have made them very nervous, even if they were going to go for broke in developing a nuclear capability.

But they didn’t seem very nervous. They seemed to be acting as if they had no fear of a war breaking out. It wasn’t just the many photos of Kim Jong Un smiling that gave this impression. It was that the North Koreans moved forward with their program regardless of American and possible Chinese pressure.

Another Player Enters the Game

A couple of weeks ago, the reason for their confidence became evident. First, US President Donald Trump tweeted a message to the South Koreans accusing them of appeasement. In response, the South Koreans released a statement saying South Korea’s top interest was to ensure that it would never again experience the devastation it endured during the Korean War. From South Korea’s perspective, artillery fire exchanges that might hit Seoul had to be avoided. Given the choice between a major war to end the North’s nuclear program and accepting a North Korea armed with nuclear weapons, South Korea would choose the latter.

With that policy made public, and Trump’s criticism of it on the table, the entire game changed its form. The situation had been viewed as a two-player game, with North Korea rushing to build a deterrent, and the US looking for the right moment to attack. But it was actually a three-player game, in which the major dispute was between South Korea and the United States.

The US could have attacked the North without South Korea’s agreement, but it would have been substantially more difficult. The US has a large number of fighter jets and about 40,000 troops based in the South. South Korean airspace would be needed as well. If Seoul refused to cooperate, the US would be facing two hostile powers, and would possibly push the North and the South together. Washington would be blamed for the inevitable casualties in Seoul. The risk of failure would pyramid.

With the South making it clear that it couldn’t accept another devastating war on the peninsula, the war option was dissolving for the United States. When we consider North Korea’s confidence now, it is completely explicable. Assuming the South hadn’t told the North its position, Pyongyang’s intelligence service certainly picked it up, given the various meetings being held. I thought these meetings were about war plans, but in retrospect they were about pressuring and cajoling South Korea to accept the plans. Another indicator I missed was a general absence of South Korean preparations for war and an odd calm among the public. The US was leaning forward, and yet there were few practice evacuations, as if the South did not expect war.

The key element I missed was that South Korea’s overriding imperative was the avoidance of war. It wasn’t happy with North Korea’s programs, but it was not prepared to sustain the kind of casualties an attack on North Korea would precipitate in the South, and especially not the possibility that, like other American wars, a quick intervention would turn into a long and limitless war.

Other Options

For the United States, a nuclear North Korea is still anathema, but war is less of an option. One solution would be to increase the isolation of the North, but there is little that can be done to isolate Pyongyang more than it already is. Another solution would be to convince China to bring overwhelming pressure on North Korea. But in exchange for their cooperation, the Chinese will demand massive concessions. Some will be about trade, others about the South China Sea and US forces in South Korea. Trump will be traveling to China, likely in November, to continue negotiations. In the meantime, South Korea remains opposed to war on the peninsula, and that explains why the US is going after South Korea on steel.

We got the crisis I predicted, but the war that seemed so likely has become an enormously more complex issue… though still a possibility. If North Korea appears too immediately threatening, if China is unwilling or incapable of persuading the North, or if the United States simply decides that it cannot tolerate the risk posed by North Korea, then war is possible. But the geometry of that war will be very different than it first appeared to me.

Pension Storm Warning

By John Mauldin

(This column refers to the USA but is applicable to much of the western world. Happily South Africa has (for now) fully funded pension schemes. RAC)

This time is different are the four most dangerous words any economist or money manager can utter.

We learn new things and invent new technologies. Players come and go. But in the big picture, this time is usually not fundamentally different, because fallible humans are still in charge.

(Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart wrote an important book called This Time Is Different on the 260-odd times that governments have defaulted on their debts; and on each occasion, up until the moment of collapse, investors kept telling themselves “This time is different.” It never was.)

Nevertheless, I uttered those four words and I stand by them. In the next 20 years, we’re going to see changes that humanity has never seen before, and in some cases never even imagined, and we’re going to have to change. I truly believe this. We have unleashed economic and technological forces we can observe but not entirely control.

Today we will zero in on one of those forces “the bubble in government promises,” which I think is arguably the biggest bubble in human history. Elected officials at all levels have promised workers they will receive pension benefits without taking the hard steps necessary to deliver on those promises. This situation will end badly and hurt many people. Unfortunately, massive snafus like this rarely hurt the politicians who made those overly optimistic promises, often years ago.

Earlier this year I called the pension mess “The Crisis We Can’t Muddle Through.” Reflecting since then, I think I was too optimistic. Simply waiting for the floodwaters to drop down to muddle-through depth won’t be enough. We face an entire new ocean, deeper and wider than we can ever cross unaided.

Storms from Nowhere?

This year marks the first time on record that two Category 4 hurricanes have struck the US mainland in the same year. Worse, Harvey and Irma landed directly on some of our most valuable and vulnerable coastal areas. So now, in addition to all the problems that existed a month ago, the US economy has to absorb cleanup and rebuilding costs for large parts of Texas and Florida, as well as our Puerto Rico and US Virgin Islands territories.

Now then, people who live in coastal areas know full well that hurricanes happen – they know the risk, just not which hurricane season might launch a devastating storm in their direction. In a note to me about Harvey, fellow Rice University graduate Gary Haubold (1980) noted just how flawed the city’s assumptions actually were regarding what constitutes adequate preparedness. He cited this excerpt from a recent

Los Angeles Times article:

The storm was unprecedented, but the city has been deceiving itself for decades about its vulnerability to flooding, said Robert Bea, a member of the National Academy of Engineering and UC Berkeley emeritus civil engineering professor who has studied hurricane risks along the Gulf Coast.

The city’s flood system is supposed to protect the public from a 100-year storm, but Bea calls that “a 100-year lie” because it is based on a rainfall total of 13 inches in 24 hours.

“That has happened more than eight times in the last 27 years,” Bea said. “It is wrong on two counts. It isn’t accurate about the past risk and it doesn’t reflect what will happen in the next 100 years.” (Source)

Anybody who lives in Houston can tell you that 13 inches in 24 hours is not all that unusual. But how do Robert Bea’s points apply to today’s topic, public pensions? Both pension plan shortfalls and hurricanes are known risks for which state and local governments must prepare. And in both instances, too much optimism and too little preparation ultimately have devastating results.

Admittedly, public pension liabilities don’t come out of nowhere the way hurricanes seem to – we know exactly where they will strike. In many cases, we know approximately when they’ll strike, too. Yet we still let our elected officials make impossible-to-fulfill promises on our behalf. The rest of us are not so different from those who built beach homes and didn’t buy hurricane or storm surge insurance. We just face a different kind of storm.

Worse, we let our government officials use predictions about future returns that are every bit as unrealistic as calling a 13-inch rain in Houston a 100-year event. And while some of us have called pension officials out, they just keep telling lies – and probably will until we reach the breaking point.

Puerto Rico is a good example. The Commonwealth was already in deep debt before Irma blew in – $123 billion worth of it. There’s simply no way the island can repay such a massive debt. Creditors can fight in the courts, but in the end you can’t squeeze money out of plantains or pineapples. Not enough money, anyway. Now add Irma damages, and the creditors have even less hope of recovering their principal, let alone interest.

Puerto Rico is presently in a new form of bankruptcy that Congress authorized last year. Court proceedings will probably drag on for years, but the final outcome isn’t in doubt. Creditors will get some scraps – at best perhaps $0.30 on the dollar, my sources say – and then move on. We’re going to find out how strong those credit insurance guarantees really are.

“That’s just Puerto Rico,” you may say if you’re a US citizen in one of the 50 states. Be very careful. Your state is probably not so much better off. In 10 years, your state may well be in the same place that Puerto Rico is now. I’d say the odds are better than even.

Are your elected leaders doing anything about this huge issue, or even talking about it? Probably not.

As it stands now, states can’t declare bankruptcy in federal courts. Letting them do so would raises thorny constitutional issues. So maybe we’ll have to call it something else, but it’s going to end the same way. Your state’s public-sector retirees will not get what they were promised, and they won’t take the outcome kindly.

Blood from Turnips

Public sector bankruptcy, up to and including state-level bankruptcy, is fundamentally different from corporate bankruptcy in ways that many people haven’t considered. The pension crisis will likely expose those differences as deadly to creditors and retirees.

Say a corporation goes bankrupt. A court will take all its assets and decide how to divvy them up. The assets are easy to identify: buildings, land, intellectual property, cash, etc. The parties may argue over their value, but everyone knows what the assets are. They won’t walk away.

Not so in a public bankruptcy. The primary asset of a city, county, or state is future tax revenue from households and businesses within its boundaries. The taxpayers can walk away. Even without moving, they can bypass sales taxes by shopping elsewhere. If property taxes are too high, they can sell and move. When they take a loss on the sale, the new owner will have established a property value that yields the city far less revenue than it used to receive.

Cities and states don’t have the ability to shed their pension liabilities. They are stuck with them, even as population and property values change.

We may soon see an example of this in Houston. Here in Texas, our property taxes are very high because we have no income tax. Your tax is a percentage of your home’s taxable value. So people argue to appraisal boards that their homes are falling apart and not worth anything like the appraised value. (Then they argue the opposite when it’s time to sell the home.)

About 200 entities in Harris County can charge taxes. That includes governments from Houston to Baytown to Hedwig Village, plus 20 independent school districts.

There’s a hospital district, port authority, several college districts, the flood control district, a multitude of utility districts, and the Harris County Department of Education. Some homes may fall within 10 or more jurisdictions.

What about those thousands of flooded homes in and around Houston; how much are they worth? Right now, I’d say their value is zero in many cases. Maybe they will have some value if it’s possible to rebuild, but at the very least they ought to receive a sharp discount from the tax collector this year.

Considering how many destroyed or unlivable properties there are all over South Texas, I suspect cities and counties will lose billions in revenue even as their expenses rise. That’s a small version of what I expect as city and state pension systems all over the US finally face reality.

Here in Dallas I pay about 2.7% in property taxes. When I bought my home over four years ago, I checked our local pension and was told we were 100% funded. I even mentioned in my letter that I was rather surprised. Turns out they lied. Now, realistic assessments suggest they will have to double the municipal tax rate (yes, I said double) to be able to fund fire and police pension funds. Not a terribly popular thing to do. At some point, look for taxpayers to desert the most-indebted cities and states. Then what? I don’t know. Every solution I can imagine is ugly.

Promises from Air

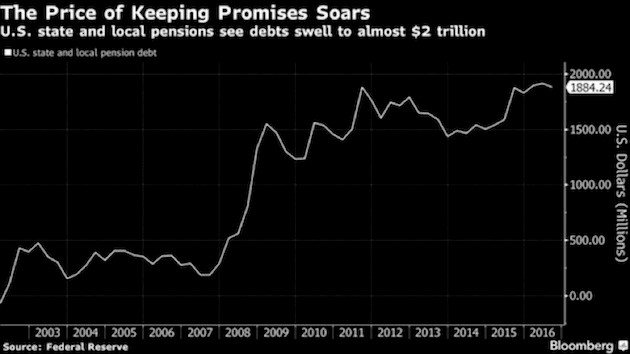

Most public pension plans are not fully funded. Earlier this year in “Disappearing Pensions” I shared this chart from my good friend Danielle DiMartino Booth:

Total unfunded liabilities in state and local pensions have roughly quintupled in the last decade. You read that right – not doubled, tripled or quadrupled: quintupled. That’s nice when it happens on a slot machine, not so nice when it’s money you owe.

You will also notice in the chart that much of that change happened in 2008. Why was that? That’s when the Fed took interest rates down to nearly zero, meaning it suddenly took more cash to fund future payments. Also, some strapped localities conserved cash by promising public workers more generous pension benefits in lieu of pay raises.

According to a 2014 Pew study, only 15 states follow policies that have funded at least 100% of their pension needs. And that estimate is based on the aggressive assumptions of pension funds that they will get their predicted rate of returns (the “discount rate”).

Kentucky, for instance, has unfunded pension liabilities of $40 billion or more. This month the state budget director notified local governments that pension costs could jump 50-60% next year. That’s due to a proposed reduction in the system’s assumed rate of return from 7.5% to 6.25% – a step in the right direction but not nearly enough.

Think about this as an investor. Do you know a way to guarantee yourself even 6.25% average annual returns for the next 10–20 years? Of you don’t. Yes, some strategies have a good shot at doing it, but there’s no guarantee.

And if you believe Jeremy Grantham’s seven-year forecasts (I do: His 2009 growth forecast was spot on), then those pension funds have very little hope of getting their average 7% predicted rate of return, at least for the next seven years.

Now, here is the truth about pension liabilities. Let’s assume you have $1 billion in funding today. If you assume a 7% compound return – about the average for most pension funds – then that means in 30 years that $1 million will have grown to $8 billion (approximately). Now, what if it’s a 4% return? Using the Rule of 72, the $1 billion grows to around $3.5 billion, or less than half the future assets in 30 years if you assume 7%.

Remember that every dollar that is not funded today means that somewhere between four dollars and eight dollars will not be there in 30 years when somebody who is on a pension is expecting to get it. Worse, without proper funding, as the fund starts going negative, the funding ratio actually gets worse, sending it into a death spiral. The only way to bring it out of the spiral is with huge cuts to other needed services or with massive tax cuts to pension benefits.

The State of Kentucky’s unusually frank report regarding the state’s public pension liability sums up that state’s plight in one chart:

The news for Kentucky retirees is quite dire, especially considering what returns on investments are realistically likely to be. But there’s a make or break point somewhere. What if pension plans must either hit that 6% average annual return for 2018–2028 or declare bankruptcy and lose it all?

That’s a much greater problem, and it’s a rough equivalent of what state pension trustees have to do. Failing to generate the target returns doesn’t reduce the liability. It just means taxpayers must make up the difference.

But wait, it gets worse. The graph we showed earlier stated that unfunded pension liabilities for state and local governments was $2 trillion. But that assumes an average 7% compound return. What if we assume 4% compound returns? Now the admitted unfunded pension liability is $4 trillion. But what if we have a recession and the stock market goes down by the past average of more than 40%? Now you have an unfunded liability in the range of $7–8 trillion.

We throw the words a trillion dollars around, not realizing how much that actually is. Combined state and local revenues for the US total around $2.6 trillion. Following the next recession (whenever that is), the unfunded pension liabilities for state and local governments will be roughly three times the revenue they are collecting today, and that’s before a recession reduces their revenues. Can you see the taxpayer stuck between a rock and a hard place? Two immovable objects meeting? The math just doesn’t work.

Pension trustees don’t face personal liability. They’re literally playing with someone else’s money. Some try very hard to be realistic and cautious. Others don’t. But even the most diligent can’t control when the next recession comes, or when the stock market will crash, leaving a gaping hole in their assets while liabilities keep right on rising.

I have had meetings with trustees of various government pensions. Many of them want to assume a more realistic discount rate, but the politicians in their state literally refuse to allow them to assume a reasonable discount rate, because owning up to reality would require them to increase their current pension funding dramatically. So they kick the can down the road.

Intentionally or not, state and local officials all over the US made pension promises that future officials can’t possibly keep. Many will be out of office when the bill comes due, protected from liability by sovereign immunity.

We are starting to see cities filing for bankruptcy. That small ripple will be a tsunami within 7–10 years.

But wait, it gets still worse. (Do you see a trend here?) Many state and local governments have actually 100% funded their pension plans. Some states and local governments have even overfunded them – assuming they get their projected returns. What that really means is that the unfunded liabilities are more concentrated, and they show up in unlikely places. You think Texas is doing well? Look at some of our cities and weep. Look, too, at other seemingly semi-prosperous cities all over the country. Do you think the suburbs of Dallas will want to see their taxes increased to help out the city? If you do, I may have a bridge to sell you – unless you would rather have oceanfront properties in Arizona.

This issue is going to set neighbour against neighbour and retirees against taxpayers. It will become one of the most heated battles of my lifetime. It will make the Trump-Clinton campaigns look like a school kids’ tiddlywinks smackdown.

I was heavily involved in politics at both the national and local levels in the 80s and 90s and much of the 2000s. Trust me, local politics is far nastier and more vicious. And there is nothing more local than police and firefighters and teachers seeing their pensions cut because the money isn’t there. Tax increases of up to 100% are going to become commonplace. But even these new revenues won’t be enough… because we will be acting with too little, too late.

This is the core problem. Our political system gives some people incentives to make unrealistic promises while also absolving them of liability for doing so. It also places the costs of those must-break promises on innocent parties, i.e. the retirees who did their jobs and rightly expect the compensation they were told they would receive.

So at its heart the pension crisis is really not a financial problem. It’s a moral and ethical problem of making and breaking promises that profoundly impact people’s lives. Our culture puts a high value on integrity: doing what you said you would do.

We take a job because the compensation package includes x, y and z. Then someone says no, we can’t give you z, so quit and go elsewhere.

The pension problem is going to get worse as more and more retirees get stuck with broken promises, and as taxpayers get handed higher and higher bills. These are irreconcilable demands in many cases. It’s not possible to keep contradictory promises.

What’s the endgame? I think much of the US will end up like Puerto Rico. But the hardship map will be more random than you can possibly imagine. Some sort of authority – whether bankruptcy courts or something else – will have to seize pension assets and figure out who gets hurt and how much. Some courts in some states will require taxes to go up. But courts don’t have taxing authority, so they can only require cities to pay, but with what money and from whom?

In many states we literally don’t have the laws and courts in place with authority to deal with this. And just try passing a law that allows for states or cities to file bankruptcy in order to get out of their pension obligations.

The struggle will get ugly, and innocent people on both sides will be hurt. We hear stories about retired police chiefs and teachers with lifetime six-digit pensions and so on. Those aberrations (if you look at the national salary picture) are a problem, but the more distressing cases are the firefighters, teachers, police officers, or humble civil servants who served the public for decades, never making much money but looking forward to a somewhat comfortable retirement. How do you tell these people that they can’t have a liveable pension? We will see many human tragedies.

On the other side will be homeowners and small business owners, already struggling in a changing economy and then being told their taxes will double. This may actually happen in Dallas; and if it does, we won’t be alone for long.

The website Pension Tsunami posts scores of articles, written all across America, about pension problems. We find out today that in places like New York and Chicago and Cook County, pension funds have more retirees collecting than workers paying into the fund. There are more retired cops in New York and Chicago than there are working cops. And the numbers of retirees just keep growing. On an individual basis, it is smart for the Chicago police officer to retire as early possible, locking in benefits, go on to another job that offers more retirement benefits, and round out a career by working at least three years at a private job that qualifies the officer for Social Security. Many police and fire pensions are based on the last three years of income; so in the last three years before they retire, these diligent public servants work enormous amounts of overtime, increasing their annual pay and thus their final pension payouts.

As I’ve said, this is the crisis we can’t muddle through. While the federal government (and I realize this is economic heresy) can print money if it has to, state and local governments can’t print. They actually have to tax to pay their bills. It’s the law. It’s also an arrangement with real potential to cause political and social upheaval that Americans have not seen in decades. The storm is only beginning. Think Hurricane Harvey on steroids, but all over America. Of all the intractable economic problems I see in the future (and I have a vivid imagination), this is the most daunting.

US View: How to beat the banks at their own game

By Patrick Watson

When it comes to public sentiment, banks and Congress have a lot in common.

People tell pollsters they dislike Congress in general, but they keep re-electing their own representative and senators.

Similarly, people tend to like their own bank and disapprove of others, according to the latest American Banker/Reputation Institute survey.

One glaring exception: Wells Fargo (WFC). Pretty much no one likes Wells Fargo since last year’s revelation that the bank’s staff had opened millions of false accounts to meet ambitious sales targets.

I said at the time there’s never just one cockroach. Turn on the lights, and you’ll see more scurrying away.

That proved true for Wells Fargo. It’s now embroiled in several other scandals, like forcing customers to buy car insurance they didn’t need. Other banks may have similar issues.

The banking giants get away with these things because people feel powerless against them, but now there’s a new way to beat the banks at their own game—and keep some of those handsome profits for yourself.

Shedding Layers

Economists love to use fancy words for simple concepts, like disintermediation. It simply means “removing intermediaries” or what we used to call “middlemen.”

In the 1970s, if you needed a new refrigerator, you would buy one at your local appliance store. The store bought it from a wholesale distributor, which got it from a manufacturer’s rep, who took it on consignment from the manufacturer. Every one of those intermediaries had to make money.

Today, if you want a refrigerator, you go to a big-box store like Sears (SHLD), Best Buy (BBY), or Home Depot (HD), or even order one from Amazon and save on shipping costs. The store—whether brick and mortar or online—acquired the fridge directly from the manufacturer. Two or three distribution layers are gone now.

On balance, that’s a good thing. Extra layers are wonderful with dessert; for the economy, they’re not so sweet.

Photo: Kimberly Vardeman via Flickr

Disintermediation allocates labor and capital more efficiently, helping the economy grow. Which brings us to banks.

Being a middleman is the main reason banks exist. Their core function is to stand in between two groups:

- People with money to lend

- People who need to borrow

Contrary to what many folks think, your savings account or certificate of deposit is not in the bank for safekeeping. It’s in the bank because the bank has borrowed your cash. That’s why deposits go on the liability side of the bank’s balance sheet.

So if you have a bank account, you’re automatically a lender. You might also be a borrower if you have a credit card, mortgage, or auto loan.

The bank profits by charging the borrower a higher interest rate than it pays the lenders (aka depositors). Say you get 1% on your CD, and the bank lends your cash to someone else for 7%. The difference between the two, the net interest margin, is how the bank makes its money.

But what if there were a way for borrowers and lenders to find each other and cut out the middleman?

Peer to Peer

The new way to be your own bank is as simple as it is ingenious. It’s called peer-to-peer (P2P) lending. Using any of several online platforms, both lenders and borrowers can transact loans directly.

If you have money to lend, you can invest in a great variety of loans from prescreened borrowers. You can dial the risk level up or down by allocating to borrowers with higher or lower credit scores.

Borrowers win too, by paying lower interest rates. The losers are banks, which don’t get their usual piece of the action.

Here’s an illustration of the difference at Lending Club, one of the largest P2P platforms.

With the bank out of the equation, the borrower’s rate drops and the lender’s return goes up. In this example, the net interest margin drops from 20.64% to only 6.2%. That’s disintermediation at work.

The results aren’t always so dramatic, but it can still make a noticeable difference on both sides of a loan. And it can be a great portfolio diversifier if you already have stock or bond investments.

Of course, rates go up and down over time, but P2P lending can earn investors a higher yield than most other fixed-income instruments, without higher risks. I know people who make 5–7% annual returns.

7% Yields in a 2% World

Does P2P lending have a downside, compared to banks? Yes, and it’s a big one: deposit insurance. The FDIC won’t be there to save you if your loans default.

On the other hand, you won’t have bankers taking crazy trading risks with your money, as often happens now. So that partially reduces the need for deposit insurance.

Still, you don’t want to do this with money you absolutely can’t lose. If that’s your situation, better stick with insured banks.

Liquidity is another issue. You make loans for fixed time periods, anywhere from a year up to five years. Your cash is tied up for the loan term. You might be able to sell your loans to another investor, but don’t count on it.

You also depend on your borrowers to pay you back. They can always default, for all kinds of reasons. Maybe they lose their job or get hit by medical bills. Stuff happens. The platforms will help you try to collect, but it’s not guaranteed. And if we get into another recession, default rates will likely go up.

For more on P2P lending, check out my in-depth special report, The New Asset Class That Helps Investors Earn 7% Yields in a 2.5% World.

For more on P2P lending, check out my in-depth special report, The New Asset Class That Helps Investors Earn 7% Yields in a 2.5% World.

My colleague Stephen McBride and I pulled together all the background information you need to know, including specific tips to get you started.

You can get your free copy of the report here.

And just so you know: I am not getting paid by the P2P industry, so you won’t find a sales pitch for Lending Club or any of its competitors in the report.

Personally, I like P2P lending because it’s a win-win for both lenders and borrowers.

Sure, the banks don’t like this idea. But if your bank is like Wells Fargo, you don’t owe it any favors.