The Investor September 2016

Trusts in SARS sights

by Richard Cluver

Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan has long signalled his dislike of trusts which, he has made clear, he regards as devices employed by the wealthy to avoid taxes. And if proposals forwarded to the minister by the Davis Commission in July are brought into law, the financial position of trust beneficiaries could become very difficult indeed.

The problem facing investors who went the route of creating a family trust which, until a few years ago was universally regarded as the prudent way to ensure that one’s savings were preserved for the benefit of widows and children, is that the introduction of capital Gains taxation has made it both increasingly difficult to properly manage share portfolios of any description and particularly difficult for the beneficiaries of trusts.

Consider the current position of a trust founded as recently as 12 years ago and consisting of just six shares. I have listed them with, in brackets, their percentage capital gain since then: Hyprop (1325%) Naspers (537%) Mr Price (557%) City Lodge (304%) Discovery (367%) and FirstRand (622%). The dilemma of the trust beneficiaries is immediately clear. Since April last year it has been obvious that Mr Price, a former darling of the investment community, has fallen out of favour in the marketplace. From a peak value of R282.80 in April 2015, the shares have fallen to date to R150 and ShareFinder projects with better than 90 percent forecast accuracy that they could be standing at R124 by next May.

When Mr Price was bought back in 2002 the shares were standing at R5.91 and, had our trust beneficiary concluded that it was time to get rid of them when the first writing was on the wall, the effective gain in value of the shares would have been R276.09 per share which would have attracted capital gains tax at an effective rate of 27.306 percent which would strip the portfolio of R75. 113. Understandably, South African investors have accordingly been reluctant to act to dispose of potential underperformers in their portfolios which has, in the long-term spelt disaster for those seeking to ensure a comfortable retirement.

Elsewhere in the developed world, capital gains tax does not apply provided the proceeds of an asset disposal are shown to have been re-invested within a reasonable period of time, but NOT in South Africa. There was, however, a partial way around this problem inasmuch as one was allowed to “trickle down” the proceeds to a beneficiary such as an unemployed spouse or a child with no taxable income in which case the minimum tax threshold of R73 650 currently applies. Thus, assuming in the example that the original purchase represented a sum of R10 000 invested into Mr Price shares in 2002, the effective gain would have been R467 157, and an investor with a wife and five children could have divided this sum between them and accordingly incurred no tax at all.

The Davis Commission however, proposes that such benefits will no longer be allowed and the gain would accordingly be taxed at an effective 41 percent within the Trust, stripping away R191 534 of the investment sum.

And now it is likely to get even worse. Dividend income earned by individuals and trusts currently attracts a withholding tax of at 15 percent and the balance is not further taxed. However, if the Davis Commission proposals are enacted, it appears as if this balance of 85 percent would be taxed again in the hands of the beneficiary at 41 percent. Thus, it can be seen that an individual who set up a family trust to take care of himself and his wife in their retirement would currently receive R85 000 a year for every R100 000 of dividend income earned but once the Davis Commission recommendations take effect they would be left with only R50 150; enough to effectively destroy most retirement plans.

Only two, somewhat drastic solutions appear possible. Many beneficiaries of trusts are probably in these circumstances considering leaving the country for tax refuges like Mauritius where a flat tax of 15 percent would apply to them. However, they would still face a capital gains problem if they sought to liquidate their family trust in order to realise their investment capital and emigrate. The answer, I believe, would be to loan the assets of the trust of a managed unit trust within which the portfolio managers are free to dispose of underperforming shares without attracting capital gains tax which would then only apply if the beneficiaries needed to sell any units in order to release capital.

To that end I and my associates are currently investigating the creation of such a unit trust managed by the ShareFinder system which has shown itself able to consistently deliver record-breaking capital and dividend growth. Watch this space!

China facing full-blown banking crisis

By Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

Originally published in the Telegraph, Sept. 19, 2016

China has failed to curb excesses in its credit system and faces mounting risks of a full-blown banking crisis, according to early warning indicators released by the world’s top financial watchdog. A key gauge of credit vulnerability is now three times over the danger threshold and has continued to deteriorate, despite pledges by Chinese premier Li Keqiang to wean the economy off debt-driven growth before it is too late.

The Bank for International Settlements warned in its quarterly report that China’s “credit to GDP gap” has reached 30.1, the highest to date and in a different league altogether from any other major country tracked by the institution. It is also significantly higher than the scores in East Asia’s speculative boom on 1997 or in the US subprime bubble before the Lehman crisis. Studies of earlier banking crises around the world over the last sixty years suggest that any score above ten requires careful monitoring. The credit to GDP gap measures deviations from normal patterns within any one country and therefore strips out cultural differences.

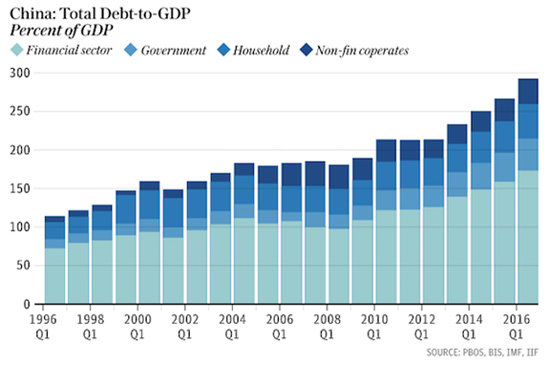

It is based on work the US economist Hyman Minsky and has proved to be the best single gauge of banking risk, although the final denouement can often take longer than assumed. Indicators for what would happen to debt service costs if interest rates rose 250 basis points are also well over the safety line. China’s total credit reached 255pc of GDP at the end of last year, a jump of 107 percentage points over eight years. This is an extremely high level for a developing economy and is still rising fast . Outstanding loans have reached $28 trillion, as much as the commercial banking systems of the US and Japan combined. The scale is enough to threaten a worldwide shock if China ever loses control. Corporate debt alone has reached 171pc of GDP, and it is this that is keeping global regulators awake at night.

The BIS said there are ample reasons to worry about the health of world’s financial system. Zero interest rates and bond purchases by central banks have left markets acutely sensitive to the slightest shift in monetary policy, or even a hint of a shift. “There has been a distinctly mixed feel to the recent rally – more stick than carrot, more push than pull,” said Claudio Borio, the BIS’s chief economist. “This explains the nagging question of whether market prices fully reflect the risks ahead.”

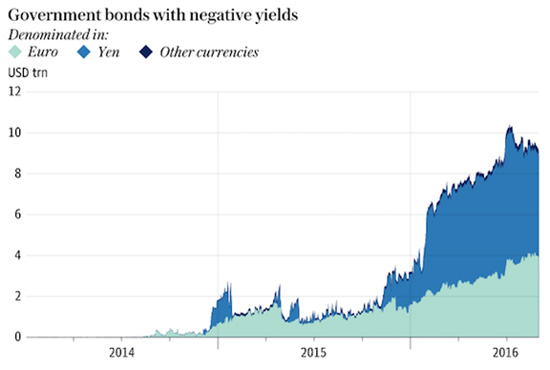

Bond yields in the major economies normally track the growth rate of nominal GDP, but they are now far lower. Roughly $10 trillion is trading at negative rates, and this has spread into corporate debt. This historical anomaly is underpinning richly-valued stock markets at time when profit growth has collapsed.

The risk is a violent spike in yields if the pattern should revert to norm, setting off a flight from global bourses. We have had a foretaste of this over recent days. The other grim possibility is that ultra-low yields are instead pricing in a slump in nominal GDP for years to come – effectively a trade depression – and that would be even worse for equities.“It is becoming increasingly evident that central banks have been overburdened for far too long,” said Mr Borio.

The BIS said one troubling development is a breakdown in the relationship between interest rates and currencies in global markets, what it describes as a violation of the iron law of “covered interest parity”. The concern is that banks are displaying a highly defensive reflex, and could pull back abruptly as they did during the Lehman crisis once they smell fear. “The banking sector may become an amplifier of shocks rather than an absorber of shocks,” said Hyun Song Shin, the BIS’s research chief.

This conflicts with what the Bank of England has been saying and suggests that recent assurances by Governor Mark Carney should be treated with caution. Yet it is China that is emerging as the epicentre of risk. The International Monetary Fund warned in June that debt levels were alarming and “must be addressed immediately”, though it is far from clear how the authorities can extract themselves so late in the day.

The risks are well understood in Beijing. The state-owned People’s Daily published a front-page interview earlier this year from a “very authoritative person” warning that debt had been “growing like a tree in the air” and threatened to engulf China in a systemic financial crisis. The mysterious figure – possibly President Xi Jinping – called for an assault on “zombie companies” and a halt to reflexive stimulus to keep the boom going every time growth slows. The article said it is time to accept that China cannot continue to “force economic growth by levering up” and that the country must take its punishment.

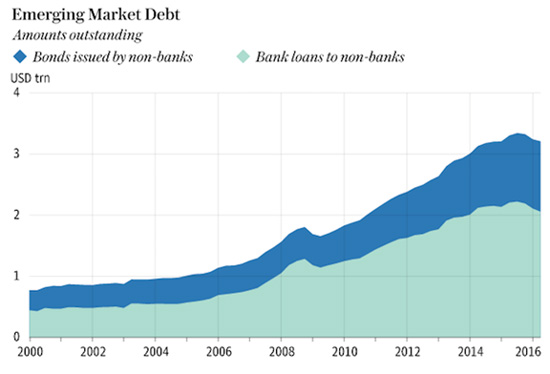

One bright spot is a repayment of foreign debt denominated in dollars. Cross-border bank credit to China has fallen by a third to $698bn since peaking in late 2014 as companies scramble to slash their liabilities before the US Federal Reserve raises rates. The tally for emerging markets as a whole has fallen by $137bn to $3.2 trillion.

China’s problem is internal credit. The risk is that a fresh spate of capital outflows will force the central bank to sell foreign exchange reserves to defend the yuan, automatically tightening monetary policy. In extremis, this could feed a vicious circle as credit woes set off further outflows.

The Chinese banking system is an arm of the Communist Party so any denouement will probably take the form of perpetual roll-overs, sapping the vitality of economy gradually.

The country was able to weather a banking crisis in the late 1990s but the circumstances were different. China was still in the boom phase of catch-up industrialisation and enjoying a demographic dividend.

Today it is no longer hyper-competitive and its work-force is shrinking, and time the scale is vastly greater.

When Trump collides globally

by Cees Bruggemans

Whatever your personal preference, this US election was for Clinton to lose and for Trump to overcome his outsider business status (a double handicap,

tripled by his unconventionality). Yet as happened with outsider Obama eight years ago, insider Clinton is fading. And Trump, against many odds, too numerable even to start on (no doubt the stuff of many books, now and to come, the New York Times columnist Maureen O’Dowds latest book and Sunday’s Charlie Rose interview on Bloomberg being just one) is the aggressive underdog seeking and finding weakness and merciless going for jugulars. Day in, day out. This isn't an expression of admiration or underwriting. It merely is observation, whether or not in fact he makes it in seven weeks time, demolishing her forever or letting her win by a sliver. But the implications of a Trump win could be earth moving, not just in the US, but like a sound burst wave traveling worldwide – economically, financially, geopolitically. The first bit could affect SA directly, and massively. Are we geared to meet incoming ordinance….? Besides needing to know whether Trump could actually overcome Clinton, we also need to know whether the US electorate would change the composition of House and Senate. Would it be a clean sweep or a two-handed situation, one that confronted Obama and defined domestic gridlock? We won't know until Nov 8. Meanwhile the Trump nails have gone into the mainmast. Tax cuts across the board, taking yet more millions of low-income US taxpayers off the books (no need to file a return) while the biggest tax cuts by value will go to the higher incomes. There will be consumer spending boosts, but there will also be guaranteed bigger budget deficits. For Republicans no issue as they reason them away, but a reality down the road nonetheless. Meanwhile, government borrowing starts at < 2% interest, a historic low, so damn the torpedoes. That story will change, but hang in there. Meanwhile, there is a lot of low-hanging fruit in crumbling US infrastructure maintenance, and even new stuff. And it is politically popular ineveryone’s backyard all over the US.

Expect a five year spending avalanche, call it pork, call it real, my inclination the latter. What are going to be the consequences?

The US economy may still have some labour slack, but its biggest slack is in business capital resources sitting in financial instruments and outlets, and not translated into fixed investment capacities, whether services (knowledge) industries or physical ones. Jump-starting that lot, however, isn't going to be a simple business, given the long-term caution playing between business ears, and considering the shrillness of the political messaging, with who-knows-what outcomes.

So some US labour and capacity overheating could result on a 12-24 month basis as capital takes its time responding to what it sees playing in its own

backyards. But that there could be an economic (and mild inflation) boost. Equity markets may conceivably love the earnings outlook implications. But the rest of the financial complex?

That takes us back to the Fed, bond and currency markets. And here comes the main interpretation mistake of the moment, like Brexit, in not taking

Trump too serious, until he overwhelms them all with his warm bomb blanket. And when he does…

It reminds in a seriously understated, distant way of Alexis de Tocqueville regarding the onset of the French Revolution (1789): ‘Never was any such

event so inevitable yet so completely unforeseen’.

I don't know who will respond first, but markets can be expected to start at midnight into the 9 Nov, as happened to Pound Sterling on Brexit. The Fed

may then require a month until early December, like BoE before her, but by then the financial landscape and its economic implications may look quite

different from what we have known through these various years.

And we certainly by then would NOT be looking at yet lower US bond yields and weaker Dollar. Instead, the only real question is to what extent markets

would take the Trump Presidency seriously, knowing by then the new composition of Congress, and any popular steamroller messaging catching fire. The

better the reception of the main messages, the more certain markets will shift in reflecting these changed realities. And the more the Fed will find itself confronted by the very realities it has been debating for the past two years and not acting on. C’est la

vie!!!

The intensity of any shock waves will of course be global as the US connects globally. And apparently not only the US. On Friday the Wall Street

Journal carried a story (next to Schauble’s picture) of German political noises starting to suggest a desire to return budget surpluses to

taxpayers as tax cuts?In a difficult election year (2017) where Merkel’s refugees are about to cause her to lose the plot? So time to go all guns blazing. On the basis of “I have principles, but if enough of you don't like them I have others…”.And if that wasn't enough, EU Commission President Juncker has recently called for a ‘common sense’ interpretation of the fiscal rules, suggesting fiscal easing is on the cards? With so much EU smoke, there is at least some fire brewing?

To have two major fiscal machines kicking in during 2017, besides minor ones in Canada and Britain in 2016 (and Japan forever), but China also still

in there somewhere, would finally change through choice (Trump) and necessity (Schauble) the global dynamic, away from an exclusive monetary reliance

to a better monetary/fiscal policy mix. If it happens….

It should shift bond yield and currency dynamics world wide, potentially shocking many smaller financially systems. It would no longer be only

ECB’s Draghi disappointing by going on standby, as he did last week, or BoJ threatening with yet more dragonian negative interest measures, and

upsetting global markets (as they may do this week, even upstaging the Fed on Wednesday), and excessive asset pricing hinting at a possible

‘Minsky’ Moment ahead (when the vertigo rubber connects with the road).

In SA, we would expect Rand/Dollar weakness and there could be upward pressure on our interest rates, long bond yields and short-term SARB rates.

Clearly, SARB is forward-looking and vigilant with its incomplete rising trajectory policy. It is not finished stabilizing our financial condition in

a dynamically changing world. A weaker Rand would mean more income power to exporters, and along with (modestly) higher interest rates (and tax

burden?) more headwinds to domestic consumers and dependent businesses.As to SA interest rate cutting in 2017, perish the thought! And overlaying it all will be our political antics, our governance reform efforts, our hard effort to get business re-engaged and improve growth prospects, and with it our credit rating verdict. My hope is that the rating agencies will be seeing and hearing too much going in the right direction (including the fiscal metrics, but short of growth which requires a much longer runway and more political change) to junk us in December. Instead, I expect yet more leeway, if accompanied with yet more rating agency exasperation but that comes with the territory.

Then again, the global shock waves likely to be unleashed by a Trump and Merkel fiscal combo could give too many financial capital market

cross-currents even for us, and up our risk profile too far for the rating agencies to hold back. But in that case it is the changing world responding

to our weak dynamics, rather than us committing ritual political hara-kiri that does the job on our rating.

A strange conflagration of potential events.

SA Reprieve resumes by Cees Bruggemans

Life is full of surprises. That is what makes it interesting, but also unpredictable. I had long walked around with the idea of a hurricane assaulting

us, thinking of 2013-2015, with a final Zuma inspired Nene spout. But after that we seemed to enter the eye of the hurricane – more benign

conditions, the Fed capitulating, and we cleaning up some unfinished business at home.

But the problem of a hurricane is that it is a rigid concept. The second half of the storm has to come around, led by the Fed(?) or Zuma(?) or both,

pummeling us with 200km winds anew. Ready to bury yourself. A lot more Rand weakness, higher interest rates, more handwringing generally.

In the event, it was the wrong concept. The reprieve of 2016 gave us a very benign Fed and lifted pressure on us, Rand firming. We then in short order

in a matter of months saw events play out whose script would have been difficult to predict ahead of time. Brexit was a shock, but it was a global bond positive shock. Our local elections were a positive development for democracy. We then got the assault on

Gordhan, again. But in the body politics things seemed to be going their own way. The courts were busy culling unfit civil servants, and Gordhan

seemed to carry on. No guarantee that, but there seemed to be a line here. The Moody's sentiments last week seems to have swayed a lot of observers,

but then the proximity of the Fed decision and global capital flows basically overwhelmed all.

We are not in an eye and not in a hurricane, though the Zuma era may still have its final surprises. The Fed has lowered its long-term rate prognosis

drastically, making her progress through 2017-2019 likely very benign. Unless of course spiked by a President Trump. But that is a future headache.

A very gradually normalising Fed is a historic oddity. So perhaps that should remain a warning. That storm warning hasn't quite gone away. And you

notice it in the demeanor of the SARB. Rates may have peaked unless they haven't. When last did I hear that one?

What I like about the next few months is that though the Fed will probably lift in December, its trajectory advice is so low it keeps everybody on

board. Locally, Treasury is about to deliver the numbers it has promised all along, despite a difficult year. And there should be some legal and

governance movement, in labour, mining, SOEs. Enough to keep the rating agencies on board.

What I don't like is the next US President or a global shock. That could rattle markets, and of course the Fed. And also our squatting political elite

gives little inkling of wanting to move on. That is most worrying, for how do you get change if squatter elites at the top of political pinnacles

refuse to make way? They are enjoying themselves far too much to even consider relocating…..

Old worries dressed up in new clothes, but upon us potentially within months. So the worry remains that the 2016 reprieve we enjoyed and favourable

global influences may still somehow evaporate suddenly. And if not that, to encounter the snarl and bite from the Zuma patronage networks.

Still, we got this far through 2016, and despite a few ups and downs, it has been remarkable just how friendly this year has been compared to the

nightmare of 2015. No guarantees about the new year, 2017. Probably more surprises.

“You had better pay attention: This could be the final nail in the coffin of higher education

A sizeable portion of “the students” are not students at all, but everything from gangsters to anarchists”

Jonathan Jansen

TO THE rational mind, the new outbreak of student protests makes no sense. The minister of higher education‘s announcement this week provides unprecedented levels of financial assistance to the children of the poor and to the “missing middle”, those students too well-off to qualify for government bursaries but too poor to fund their own studies.

All university leaders, and any number of analysts, greeted this official statement with relief.

Not the protesting students. They want free education, period, and so the disruptions, the intimidation, the violence start all over again as this group of activists relish their new-found power — they can shut down a university.

The public has many other issues that hold its attention, such as the deaths of kwaito star Mandoza and veteran journalist Allister Sparks, or the Brangelina divorce. We are not paying attention to what might well be the final nail in the coffin of higher education, and a minority of students are trashing higher education for the poor and the destiny of our best universities. Let‘s take a closer look.

Many research publications have shown that across-the-board free education benefits only one group — the middle classes and the wealthy. Or, in even more stark terms, the “free education” demanded by the protesters would widen the gap between rich and poor, causing even greater inequality in a society with arguably the highest Gini coefficient in the world.

But nothing to worry about, we are in an era of post-truth politics, as one commentator called it. In this age of politics as theatre, it does not matter if the lines between fact and fiction become blurred in the spectacle of public performance.

The media so easily claims that “the students” shut down the campuses. Look carefully, and you will see it is a very small minority of the students on campuses with more than 20000 and often 30000 or 40000 students.

So who are “the students”? A fraction of enrolments, a spectacularly noisy few whose contribution to our future is based on media sound-bites rather than incisive analysis.

Even more disturbing, a sizeable portion of “the students” are not students at all, but everything from gangsters to anarchists, who have no connection to higher education.

Which raises the question: how can such a small minority determine the future of the silent majority? They cannot do it without massive intimidation and the constant threat of violence. That is why they storm classes, threaten staff and students, and frogmarch those who want to learn towards a central protesting space.

The minority need a crowd for the media spectacle, otherwise the protesting group looks disappointingly thin.

If a campus-wide referendum were held to ask whether classes should be shut down, a majority would say “no”, showing up the fact that universities are being held to ransom by a noisy minority.

But take a closer look at “the students”. Their leaders, in most cases, are from the middle class. These are young people who can afford a shutdown. They are privileged and come from good schools. With their social capital they can make up lost time and cram successfully for year-end examinations.

The students whose lives they are busy destroying are the very people they claim to speak for — the poorest of the poor.

These are vulnerable students who form part of that majority who drop out or who struggle to finish a three-year degree within six years. It is the poor student from Thaba Nchu or Orange Farm or Thohoyandou or Mount Frere or Manenberg. For this student, every hour spent in class matters, as do extra tutorials in a difficult subject. The disruption of a day or two or, heaven forbid, a week, could end his or her academic prospects for the year effectively making them part of the millions of NEETs — young people Not in Education, Employment or Training.

The fact that the protests happen on the eve of the final examinations is catstrophic for these students. But who cares?

The minority of protesters can live out their dreams of a self-declared revolution with disregard for the harsh, lived realities of the majority of students.

What the minister has announced in an economy that is not growing and in a society that remains dangerously unequal, is to offer relief to the children of the poor and place, rightly so, a contributing obligation on families who can afford to pay for their children‘s studies.

Tags: The Investor September 2016