The Investor February 2021

ShareFinder’s prediction for Wall Street for the next FIVE months:

The State of Play

By Richard Cluver February 2021

I want to start with two charts that tell you something important about the current state of the global economy and why none of us are feeling in a comfortable monetary space at present.

Both details how much of all of our collective earnings is flowing to government. The first is how the situation looked 50 years ago. The colour coding for individual nations on the world map suggests that on average major world governments for whom data existed then were re-directing around 23 to 25 percent of all income to their use:

The second chart shows how the situation had changed by 2017 when the average government share had more than doubled:

Furthermore, if you think you might have escaped this inevitable trend, the following plots South African Government spending on an annual basis from 1960 to the present, a tenfold gain from R65 991-million to R655 913-million.

The South African government has been taking an ever-greater share of the economy to spend as it sees fit as the following graph indicates:

In 1960 the SA Government collected just 9.3 percent of GDP and in 2019 it collected 21.3 percent.

In 1960 the SA Government collected just 9.3 percent of GDP and in 2019 it collected 21.3 percent.

Now it is of critical importance to understand that when governments take more in taxes there is obviously less money available to spend in the private sector and so the inevitable result is a slowing economy if government does not spend it in a productive manner. So the critical issue is to what use government puts that money.

If it were to be spent upon needed infrastructure development where the knock-on effect would be job-creation, that would be a good thing. Instead, as most readers already know now that the biggest expense is the civic service pay cheque which in the last financial year cost taxpayers R745-billion or 42 percent of all its spending.

The consequence has been a dramatic loss of private sector jobs and an economy forced into recession. The rise in compensation of government employees over this period has dramatically outstripped inflation.

By way of comparison, the government spent R170-billion on salaries and wages in 2004/05. Thus the increase to R745-billion in 2018/19, represented an average annual growth rate of 11 percent a year. In contrast, the consumer price index increased by an average of 5.8 percent per year over this period.

Between the fourth quarter of 2009 and the fourth quarter of 2019, the number of civil servants in South Africa grew from 1,780,553 to 2,108,125 – an increase of 327,572. When public anger began growing as these statistics became known, the growth rate slowed. But recently it has surged once more as the following graph illustrates.

Collecting salary data is a little difficult since it is not accounted for under one single heading but rather spread across many government sectors. But one can conclude that health and education accounted for over half of the compensation budget in 2018/19. This was mostly to finance the pay of doctors, nurses and teachers.

Public order and safety – which includes personnel working in the police, correctional services and the courts – accounted for almost 20 percent of total compensation of employees.

In the 2018/2019 fiscal year the breakdown of government spending was general public services (R437 129 million or 24,4%), followed by education (R360 239 million or 20,1%), social protection (R257 429 million or 14,3%), health (R217 349 million or 12,1%), economic affairs (R175 082 million or 9,8%), public order and safety (R173 760 million or 9,7%), housing and community amenities (R71 420 million or 4,0%), defense (R46 659 million or 2,6%), recreation, culture and religion (R41 473 million or 2,3%) and environmental protection (R14 130 million or 0,8%).

Giving in to union pressure, presumably in the hope that their Tripartite Alliance partners will keep the ANC in government, presumably accounts for the reason why salaries and wages have risen so steeply as a percentage of the budget. But most taxpayers who have experienced the frustration of having to deal with public servants who are either incompetent or just plain lazy, might feel doubly aggrieved that public servants are in general far better paid than they are.

How the salary bill has been rising is well illustrated by the following graph:

Not only has the number employed soared, but the individual amounts they earn has risen even more rapidly. On average, Government workers earn 44 percent more than private sector employees.

Data from the Statistics South Africa’s Quarterly Employment Survey shows that average remuneration across 110 non-agricultural sectors and sub-sectors in 2018/19 was just under R273,000, compared with an estimated average remuneration of R352,000 for employees of national and provincial government. By National Treasury’s calculations, the actual average remuneration for these employees is even higher – around R393 000.

That’s R32 750 a month for the average civil servant while the Private Sector which actually generates the profits from which the Government gets its taxes can only afford to pay its employees an average of R22 750.

That’s how out of kilter things have become in South Africa and why so many of our skilled people have been emigrating! Research indicates, moreover, that the average South African public servant earns more than the average of 46 countries surveyed by the International Monetary Fund

Moreover, there is no evidence to suggest that this benefit is in any way matched by superior productivity. Rather the reverse is true.

Teachers’ salaries, traditionally a poorly-paid sector, when measured in purchasing power adjusted US dollars, are nearly 50 percent higher than the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development average. Yet we have one of the worst educational outcomes in the world. For example, a recent international survey found that more than three quarters of children aged nine cannot read for meaning.

This percentage is as high as 91 in Limpopo and 85in the Eastern Cape. And of 100 learners that start school, 50-60 will make it to matric, 40-50 will pass matric, and only 14 will go to university.

The Government’s Treasury is open about this wage disparity stating recently that “We estimate that public servants in national and provincial government earn about 20 percent of all wages earned in the non-agricultural formal sector,” Treasury said.

And they represent an intolerable burden upon the fiscus. To put that number into perspective, there are now 16.37-million people employed in both the formal and informal sectors of the economy, but only 6.1 million pay taxes. The largest group of taxpayers, some 2.85-million of them earn between R70 000 and R350 000 annually and collectively pay R59.96-billion in income tax which nowhere nearly pays the R745-billion salary bill of the 2.1-million public servants.

That also means there are fewer people paying income tax than the 6.5-million people who are currently unemployed in South Africa. This latter figure implies that for every man and woman and on the civil service payroll, there are another five people without any gainful employment whatsoever.

That is the real price of our misallocated spending. South Africa’s unemployment rate rose to 30.8 percent in the third quarter of 2020 from 23.3 percent in the previous period. It was the highest jobless rate since quarterly data became available in 2008, with more people searching for work amid the easing of lockdown restrictions.

It must be blindingly obvious to everyone that talk in ANC top circles of tax increases would be an absolutely astounding ask at this time. Worse, those who are proposing a wealth tax have clearly not looked at the history of countries that have tried it.

Of the 12 countries that implemented a wealth tax, only two still have one in place and none have been able to make it work. Consider the actual experience of France which was one of the first to enact a wealth tax. A subsequent 2006 article in The Washington Post titled “Old Money, New Money Flee France and Its Wealth Tax” told it all.

The article succinctly pointed out how the tax caused capital flight, brain drain, loss of jobs, and, ultimately, a net loss in tax revenue.

Among other things, the article stated, “Eric Pichet, author of a French tax guide, estimates the wealth tax earns the government about $2.6-billion a year but has cost the country more than $125-billion in capital flight since 1998.”

Examples of the fraud and malfeasance that followed in France once the wealth tax was introduced extended to the very highest levels of political power. It was first publicly revealed in 2013, when French budget minister Jerome Cahuzac was discovered shifting financial assets into Swiss bank accounts in order to avoid the wealth tax.

After further investigation, a French finance ministry official admitted, “A number of government officials minimised their wealth, by negligence or with intent … however, there are some who have deliberately tried to deceive the authorities.”

Yet again, in October 2014, France’s Finance Chairman and President of the National Assembly, Gilles Carrez, was found to have avoided paying the French wealth tax for three years by applying a 30 percent tax allowance on one of his homes. However, he had previously converted the home into an SCI; a private, limited company to be used for rental purposes even though the 30 percent allowance did not apply to SCI holdings. Carrez was one of more than 60 French parliamentarians who at the time of writing were battling with the tax offices over ‘dodgy’ asset declarations.

If Cyril Ramaphosa’s Government really wants an end to the recession and mounting unemployment, he will need to CUT both misplaced government spending and taxation so that money might flow where it can be used productively!

A re-print from Richard Cluver Predicts

Lately I have been warning that share markets everywhere are in a bubble which is the consequence of something like $14-trillion which the world’s central banks have pumped into the global marketplace to try and fend off the worst recessionary effects of the pandemic.

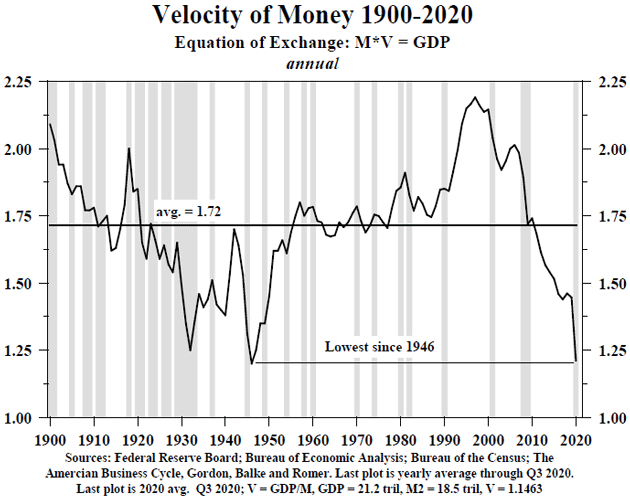

Without moving in too deeply into the arcane semi-science of monetary economics, it has long been recognised that it can take many months for such stimulation to filter all the way through to the real economy because this is a function of a variable known as the velocity of money. The concept of the latter is easily understood but measuring it is another thing which has much to do with public confidence.

Thus, for example, when the world is booming and demand for services is accordingly very high, then Joe Soap the artisan might be earning large sums in overtime money but not as a consequence seeing much of his wife and family. To make amends, he accordingly spends freely on items like bunches of flowers, boxes of chocolates and family outings whenever he has some precious leisure time to spend with them.

He feels free to spend because a lot of extra money is jingling in his pocket and he also knows there will be a lot more tomorrow. But then something like Covid-19 happens and the overtime dries up. Worse, several of his fellow workers are retrenched and he knows he is likely to be the next. So suddenly he becomes very careful with his money. Anything extra left over from buying the necessities understandably goes into clearing away debt and, once that is out of the way, into savings.

So, savings accumulate and then, suddenly there is a cure for Covid-19 when everyone has become very tired of austerity. Suddenly the dam bursts and money flows freely once again as everyone starts celebrating once more.

The concept is, as I have said, easily understood. But it is extremely difficult to plan for in advance: for example if you are an economist advising a major bank on how to place its highly-geared future positions when you have, at best, to make an educated guess in order to anticipate when a vaccine will actually roll out, particularly so at a time when the scientists are still trying to work out how to develop a vaccine. But huge money depends upon your getting it right!

And of course, if you are a central banker trying to stabilise the money supply of a nation, it gets even more tricky. If you print too much money you over-stimulate things anything like a year or so later and the nation then ends up with runaway inflation. But print too little and millions of people lose their jobs in the consequent recession which can take many more months to correct. Meanwhile the public is screaming that the Government is incompetent and you….well maybe it costs you your job!

Now what we do know is that money velocity is hugely variable so economists and central bankers usually over-compensate. But to explain velocity consider the not so long ago time of sailing ships when your grandmother ordered a roll of Damask from a merchant in Durban, it might have taken 18 months for the order to reach the mill in Manchester, be manufactured and shipped back to Durban…and another month or two before it reached Grannie’s farm somewhere on the Platteland.

Today, with internet banking, rapid supply chains, and sophisticated systems of derivatives trading, the world of finance is a very different thing than in Grannie’s time. How different is best illustrated by the dramatic Wall Street experience at the hands of the ‘Reddit Crowd’ who, a few weeks ago caused an explosion in the share price of a failing business known as GameStop. Millions of small investors, acting in internet concert, were buying and then within minutes selling again leveraged positions while, simultaneously, automated trading platforms employed by some of the mechanised hedge funds were making billions of dollar transactions in micro seconds and hedge funds were betting on a GameStop bankruptcy. It did not end well!

So how do you measure these dramatically different changes? Enter lightning-fast computers and the increasing intrusion into our everyday lives of artificial intelligence; what many people call ‘Machine Learning’ which is at the heart of the ShareFinder market prediction system.

When I built the first rudimentary ShareFinder system I used computers to apply rational fundamental tests to the balance sheet histories of stock-exchange-listed companies in order to achieve a quality ordering system and a method of determining when such shares were cyclically under or over-priced.

It made millions of Rands for early users of the system who used it on a ‘buy and hold’ basis. But to complete the system I needed to develop a means of timing when best to buy and sell these quality shares. Initially it posed a significant problem for, when I submitted all the then known charting systems to the systematic testing that the then newly-arrived desktop computers had made possible, I discovered that NONE of them really worked reliably. The most popular technical tests, if applied consistently were, I discovered, GUARANTEED to lose you money.

But there was some good and well-thought-out theory in technical analysis; only the application was invariably flawed. Computers, however, allowed me to batch-test millions of trades until I was able to derive three complementary tests of my own creation, each drawing on different types of data, which allowed me to start identifying trading points with growing accuracy and so, in the mid-1990s I began making the predictions which you see at the end of this weekly column and, back then, I would have been content to get two out of three right.

As I regularly pointed out to readers at that time, if you consistently get two out of three trades right, you are guaranteed to make good profits from trading the market. But then came Capital Gains Tax and the Government began collecting ALL of the profits that both long-term investors and short-term share traders made. Fortunately, however, ShareFinder was getting steadily better as our machine learning algorithms learned from each mistake they made. The result, as the vast majority of our users now attest, is that everyone who has used the system over the long term has, despite taxation, made huge gains.

Thus, in 2002 when I first felt confident enough to start a highly visible weekly audit of the Predicts accuracy rate, we achieved the then extraordinarily high rate of 82.36 percent for that full year. By December 2003 we had achieved 84.38 percent, by December 2004 I was making eight predictions each week compared with my original four and the accuracy rate had climbed to 86.51 percent.

But there it stuck. The programme seemed to have hit a ‘Glass Ceiling.’ In fact in 2005 the rate FELL to 85.53 percent and in 2006 it worsened to 83.03 percent and in 2007 the average was even worse at 81.66 percent, in 2008 worse still at 80.36 percent and in 2009 it fell to 80.23 percent which proved to be the bottom of the declining cycle.

Now I need to stress that I was at that time becoming increasingly worried by the steady decline. However, though I devoted considerable research to try to improve the system, I could not fault my original equations nor the process of machine-learning which I had hoped would lead to a steady increment.

Really I should not have worried because from 2010 onwards the program began eliminating its earlier errors and the numbers began steadily improving. That year the rate climbed marginally to 80.52 percent and thereafter the programme has never looked back, climbing steadily since then to reach its highest ever rate of 96.75 percent last April.

In passing, since a few systems have tried to emulate us on a global predictions basis and have all failed, we only began to understand why this was so when our overseas principles, ShareFinder International, first began re-building the system as SF6. Using the latest coding languages, they used the original predictive coding instructions that we had laid down in SF5 but were unable to replicate anything like the SF5 accuracy rates.

The reality of that exercise is, to put the analogy into layman’s terminology, the original system had constantly mutated as it learned from its mistakes. To get the new Sf6 to match the old SF5 ShareFinder International eventually did the coding equivalent of a heart transplant. The beating heart of the new system is in fact a genetically cloned version of the old one. And that is why its predictions continue – on a worldwide basis now – to forecast market direction with an accuracy rate that most hedge funds can only dream of.

Now I won’t bore you with a detailed explanation of why, but the most incomparably accurate prediction SF6 can make is its forecast of Wall Street’s Dow Jones Industrial Index which has reflected the health, or otherwise, of the New York Stock Exchange for the past 121 years. So below I have reproduced what it expects, now with an accuracy rate average of 93.37 percent, lies immediately ahead for Wall Street:

Note that ALL three indicators are predicting the end of the current 12-year long bull market though the Velocity indicator only peaks in mid-August.

Expanding just the projection graph in my final illustration below so you can see it in detail, the red trace of the short-term projection is seen to peak on Monday. But market froth is likely to last until March 5 when the medium-term projection peaks. The decline is likely to be in three phases bottoming in mid-August and it will vary from market to market as I explain at the end of this column.

Now most readers understand that when Wall Street catches a cold the rest of the world usually gets pneumonia so you would obviously like to know that ShareFinder sees our own JSE All Share Index peaking between next Wednesday (ominously that is Budget day) and March 4….but there is a one in ten chance ShareFinder is wrong!

Meanwhile markets are likely to be somewhat disconnected in the next few months so for the fine detail do read my predictions below with care!

The month ahead:

New York’s SP500: I correctly forecast gains until late May and I continue to hold that view. However, in the short-term I see declines until mid-March followed by a recovery until mid-April and then a further decline, another recovery until late May and then a long decline until mid-August.

Nasdaq: I correctly predicted that the recovery had begun and continue to see gains until the first week of April with brief weakness in early March.

London’s Footsie: I correctly predicted gains which I still see lasting until the end of April. However, in the interim I also saw a short downturn which has now begun and is likely to last until the 24th.

Germany’s Dax: I correctly predicted gains until early April and I still hold that view. However, brace yourselves for some bumps along the rise.

France’s Cac 40: I correctly predicted a slight weakening which could last until late-March ahead of the next gain to mid-April.

Hong Kong’s Hangsen: I correctly predicted medium-term gains until mid-March which are now under way. The next down-spike should begin in mid-March but be over by the first week of April ahead of gains until mid-May and then a long slide down.

Japan’s Nikkei: I correctly predicted the beginning of the next up-phase which should last until late-March before turning down till the end of April.

Australia’s All Ordinaries: I correctly predicted the market was peaking ahead of a long volatile decline which I still expect to last until late March followed by a strong up-tick to mid-May and thereafter a fresh bear phase until mid-September… and my views remain unchanged.

JSE Top 40 Index: I correctly predicted the imminence of a long declining phase until late-August. The market is now bumping its head as it tries to make a triple-top resistance level.

ShareFinder JSE Blue Chip Index: I correctly predicted the probability of the market topping out in mid-week followed by a volatile decline which has now begun and is likely to last until the end of September.

Gold Bullion: I correctly predicted a short-term decline until mid-February followed by gains which could begin today and rise in considerable volatility to peak in late October.

The Rand/US Dollar: I correctly predicted volatile gains until mid-October and continue to hold that view.

Rand/Euro: I correctly predicted resumed gains until October and I still hold that view. Short-term weakness between now and the end of March is, however likely for this is a volatile market!

The Predicts accuracy rate on a running average basis since January 2001 has been 86.06 percent. For the past 12 months it has been 93.37 percent.

What higher global inflation could mean for South Africa

by Brian Kantor

Higher commodity prices could bring about higher global inflation. That would not necessarily be bad news for South Africa.

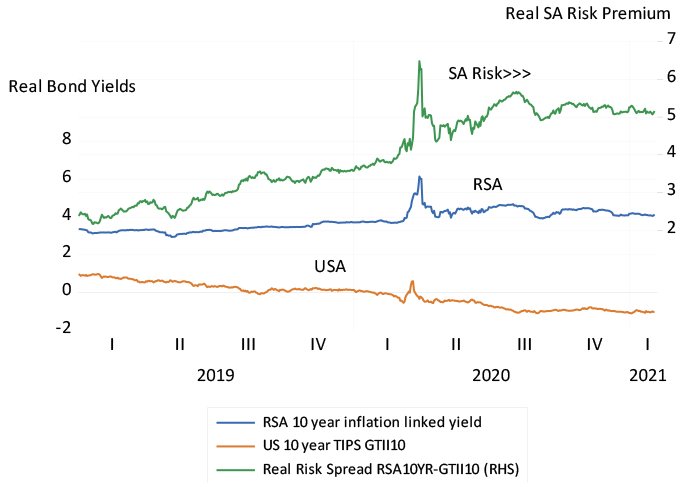

There is a hint of inflation in the frigid northern air. It’s being reflected in the long-end of the bond markets, the part of the yield curve that is vulnerable to signals of high inflation and the higher interest rates and lower bond values that follow. The compensation offered for bearing the risk that inflation may surprise on the upside is reflected in the spread between nominal and inflation-linked bond yields. These spreads have been widening in the US, and in low inflation countries like Germany and Japan.

This spread for 10-year bonds in the US was as little as 0.80% at the height of the Covid-19 crisis, was 1.63% at the end of September, and at the time of writing is at 2.14%. It has averaged 1.97% since 2010. The spread has widened because investors have forced the real yield lower, to -1.03%, further than they have pushed the nominal yield higher now, to 1.15%. This is still well below the post 2010 daily average of 2.25%.

This spread for 10-year bonds in the US was as little as 0.80% at the height of the Covid-19 crisis, was 1.63% at the end of September, and at the time of writing is at 2.14%. It has averaged 1.97% since 2010. The spread has widened because investors have forced the real yield lower, to -1.03%, further than they have pushed the nominal yield higher now, to 1.15%. This is still well below the post 2010 daily average of 2.25%.

Investors are paying up to insure themselves against higher inflation by buying inflation linkers and forcing real yields ever more negative. Clearly, the nominal yields continue to be repressed by Fed Bond buying (currently at a $120 billion monthly rate). One might think it’s easier to fight the Fed with inflation linkers, than via higher long bond yields, to which the currently low mortgage rates and a buoyant housing market are linked.

The Fed is insistent that it is not even thinking yet of tapering its bond purchases. The Treasury, now led by Janet Yellen, previously in charge of the Fed, insists that a new stimulus package of US$1.9 trillion is still needed for a US recovery.

Metal and commodity prices, grains and oil are all rising sharply off depressed levels. Industrial metals are 45% up on the lows of last year, while a broader commodity price index that includes oil is up 51% off its lows of 2020.

Metal and commodity prices, grains and oil are all rising sharply off depressed levels. Industrial metals are 45% up on the lows of last year, while a broader commodity price index that includes oil is up 51% off its lows of 2020.

These higher input prices will not automatically lead to higher prices at the factory gate or at the supermarket. Manufacturers and retailers might prefer to pass on higher input costs. But they know better than to ignore the state of demand for their goods and services. They can only charge what their markets will bear, which will depend on demand that in turn will reflect policy settings.

Higher inflation rates cannot be sustained without consistent support from the demand side of the economy. Yet supply side-driven price shocks that depress spending on other goods and services can become inflationary, if accommodated by consistently easier monetary and fiscal policy. In the 1970s, it was not the oil price shocks that were inflationary. They were a severe tax on consumers and producers in the oil importing economies, which in turn depressed demand for all other goods and services. It was the easy monetary policy designed to counter these depressing effects that led to continuous increases in most prices. That was until Fed chief Paul Volker decided otherwise and was able to shut down demand with high interest rates and a contraction in money supply growth that reversed the inflation trends for some 40 years.

Higher inflation rates cannot be sustained without consistent support from the demand side of the economy. Yet supply side-driven price shocks that depress spending on other goods and services can become inflationary, if accommodated by consistently easier monetary and fiscal policy. In the 1970s, it was not the oil price shocks that were inflationary. They were a severe tax on consumers and producers in the oil importing economies, which in turn depressed demand for all other goods and services. It was the easy monetary policy designed to counter these depressing effects that led to continuous increases in most prices. That was until Fed chief Paul Volker decided otherwise and was able to shut down demand with high interest rates and a contraction in money supply growth that reversed the inflation trends for some 40 years.

The financial markets will be alert to the prospects that demand for goods and services will prove excessive and inflationary in the years to come – and that they may not be dialled back quickly enough to hold back inflation.

There is consolation for South Africa should global inflation accelerate. It will be accompanied by higher metal prices and perhaps bring a stronger rand to dampen our own inflation. It may also help reduce the large South Africa risk premium that so weakens the incentive to undertake capital expenditure as well as the value of South African business. Our inflation-linked 10-year bonds now yield a real 4.13%, a near record 5.15 percentage points more than US inflation linkers of the same duration. Any reduction in South African risk would thus be welcome.

Inflation and Broken Windows

By John Mauldin

I’m often asked if I foresee inflation or deflation. Both are possible in their own ways, and frankly I feel a little funny telling people I think we will see both. I would just like to have a growing economy and dependable money that holds its value.

But for these letters, I have to distinguish between what I want and what I expect. The kind of stability I prefer isn’t on the menu right now. So today we will wrap up my 2021 forecast series with a look at this important debate.

Gripping Hand Update

As I have been repeating all month, anything I say about the economy or markets is subject to the coronavirus “Gripping Hand.” It greatly constrains the available options. Other possibilities open up if we manage to get and keep the virus under control.

Bluntly, conclusion first: You cannot predict inflation or deflation until you understand the extent of the virus this summer. You get to radically different outcomes, which I will discuss at the end.

The good news is that US vaccinations are accelerating. States and the federal government are working out bugs in the process. Supply constraints are easing a bit. It is still going much too slowly, but was always going to be an ordeal. With luck, everyone who wants to be vaccinated should have the chance by this summer.

Let’s look at a few charts. First of all, hospitalizations are way down. That is very good news.

Source: Justin Stebbing

Ditto for ICU patients:

The testing positivity rate and number of new cases are dropping, too. Well over 27 million people in the US have had at least one vaccine dose, with about 1.3 million more doses administered each day.

Source: Our World in Data

Here is another chart comparing the responses of various countries. We must remember that we have to vaccinate the world to keep a new strain/variant from popping out and starting this process all over again.

Source: Our World in Data

The next question is whether that will be enough. The winter surge is reversing, but the B117 and other more infectious variants could send case numbers and hospitalizations higher again, and possibly a lot higher. And even with recent improvement, the numbers are still worse than they were at last summer’s peak.

Back with a Vengeance

Thinking positively, imagine the US and other major economies vaccinate enough people in the next few months to let semi-normal life resume. We’ll still be cautious, but the generalized fear subsides enough to let us circulate again. Restaurants, hotels, airlines, and other hard-hit industries start to get back on their feet. Then what?

Scenarios like that usually point to inflation. Pent-up demand will make people spend some of the extra savings they accumulated (often via fiscal aid programs) in the last year. Possible? Yes, but I don’t expect it. I think this experience is scarring many people in the same way the Great Depression scarred our parents, giving their generation a permanently thrifty attitude. We’ll see.

But inflation can come from other directions, too. My friend Louis Gave recently described the larger forces at play.

I think inflation will come back with a vengeance. One of the key deflationary forces in the past three decades was China. I wrote a book about that in 2005; I was a deflationist then, as my belief was that every company in the world would focus on what they can do best and outsource everything else to China at lower costs. But now, we’re in a new world, a world that I outlined in my last book, Clash of Empires, where supply chains are broken up along the lines of separate empires. Let me give you a simple example: Over the past two years, the US has done everything it could to kill Huawei. It’s done so by cutting off the semiconductor supply chain to Huawei. The consequence is that every Chinese company today is worried about being the next Huawei, not just in the tech space, but in every industry. Until recently, price and quality were the most important considerations in any corporate supply chain.

Now we have moved to a world where safety of delivery matters most, even if the cost is higher. This is a dramatic paradigm shift… It adds up to a huge hit to productivity. Productivity is under attack from everywhere, from regulation, from ESG investors, and now it’s also under attack from security considerations. This would only not be inflationary if on the other side central banks were acting with restraint. But of course we know that central banks are printing money like never before.

The pandemic is clearly accelerating some pre-existing trends. Globalization was already starting to slow and possibly reverse for technological reasons. President Trump’s trade war gave more impetus to “Buy American” and “Buy Local” policies, and Biden seems intent on continuing them. And now COVID-19 gives national governments everywhere reason to be as self-sufficient as possible. Businesses feel the same pressure.

But what really matters is how the Federal Reserve responds if price inflation pushes interest rates higher. Louis believes the Fed will enact some kind of “yield curve control” to keep long-term Treasury yields near 2%. This will tank the dollar, raising inflation but sending “real” interest rates even more negative than they are now, thereby helping finance fast-growing government debt.

This scenario would be good for gold and terrible for bonds. But it’s not the only scenario, so let’s turn next to my favourite bond bull.

Broken Window Fallacy

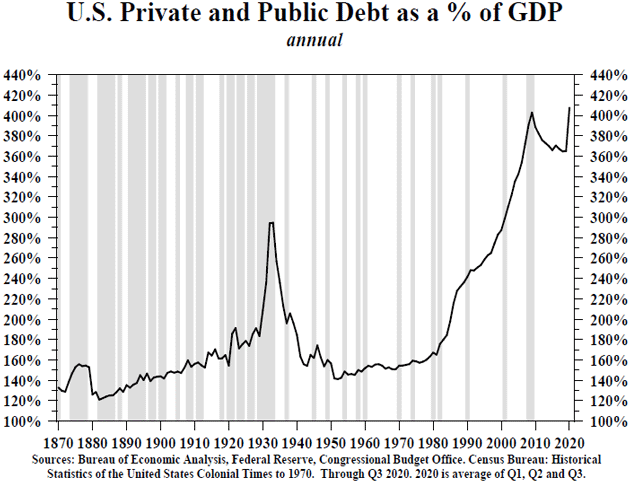

Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Investment Management has been steadfastly bullish on Treasury bonds for 39 years. He saw what Paul Volcker was doing and became a monster bond bull. He has been exactly right. His argument is really just simple math. To summarize:

- Growing public and private debt suppresses economic growth as the additional debt has a smaller and smaller effect.

- The low growth reduces velocity of money, without which sustained general inflation is impossible (though there can be inflation in some segments).

- Inflation being the major determinant of Treasury yields, those yields will move lower.

In his latest report, Lacy takes on the idea that fiscal stimulus plus recovery from the pandemic will spark inflation. He notes that any GDP growth from here won’t reflect the pandemic’s vast wealth destruction. He compares it to the famous Frederic Bastiat/Henry Hazlitt story of the broken bakery window. Fixing the damage boosts GDP, but you don’t see the other costs incurred or opportunities missed. Just as we can’t grow the economy by breaking each other’s windows, we can’t expect pandemics or other disasters to be beneficial.

He also points out (and Louis Gave does, too) that most fiscal stimulus has a small and maybe negative multiplier effect. Governments aren’t “investing” in new productive capacity or building anything new. They are simply transferring money between taxpayers, bondholders, and benefit recipients. This may be necessary in the short term, but it also misallocates resources and reduces future growth.

Lacy saves his real fire for our overuse of debt. This isn’t new but the pandemic has accelerated it.

When debt capital, like any other factor of production, is overused its marginal revenue product declines. This serves as a persistent drag on economic activity that restrains growth despite the best efforts of monetary and fiscal policy. The decline in the marginal revenue productivity of debt, due to the pandemic, must now operate with even weaker demographics around the world. The pandemic resulted in considerably lower marriage and birth rates which will have negative long-term consequences for domestic and global growth. Based upon the universally applicable production function, the capability of achieving historical rates of economic growth will be even more difficult in the years ahead.

Source: Hoisington Investment Management

The Federal Reserve is trying to stimulate an economy that already had too much debt with yet more debt. No surprise, it’s not working, though it is boosting stock/asset/housing prices. Most of their stimulus simply stays on the sidelines. This is very clear in the velocity of money, which was already trending lower but fell sharply in 2020.

Source: Hoisington Investment Management

At the most basic level, this is just plumbing. Water flows downhill. Inflation is hard to imagine unless that velocity line turns higher. But water can still splash for short periods. Velocity rose sharply in the post-WW2 years when, not coincidentally, the Fed was engaged in the kind of yield curve control Louis Gave expects.

My friend David Rosenberg agrees. He did a very interesting podcast with Grant Williams and Stephanie Pomboy. Quoting from the transcript:

David Rosenberg: So look, I would just say that you can almost dust off your slide package from 12 years ago. The same people calling for inflation now were calling for inflation back then. They’re the ones that have to answer as to why it is that inflation in the final analysis even with a stock market that quintupled, and even with a bull market and commodities, and even with 3-1/2% unemployment, we never did get the big inflation. So they’d have to come and explain why all of a sudden we’re going to get inflation in the coming cycle that we couldn’t get in the previous, not just one, not just two, but the previous three cycles.

Stephanie Pomboy: What worries me about it is that I totally agree with you on those forces of deflation or disinflationary forces that are clearly evidenced over that whole period …. But that doesn’t preclude people from getting all hot and bothered and getting chinned up on an inflation scare. They see the dollar going down, they see import prices going up and they assume, okay, well, that’s going to lead to CPI inflation, never mind that as you point out it didn’t for the last decade or even longer, but what is the possibility?

David Rosenberg: [At] the end of the day though, we have the most unpatriotic development you could ever think of, which is that Americans have paid down their credit card balances at a 14% annual rate over the past six months. It’s never happened before. And so it’s very difficult to get inflation when there’s no credit creation, which is what the money velocity numbers are telling you, or where there’s no significant wage growth. Where’s the wage growth going to come from? It’s very interesting that the same people that tell you about inflation are so bulled up on the economic outlook, they believe that full employment is still somewhere at or below 4%.

And of course the Fed’s forecast is that the next few years we’re going to get back to that magical level below 4%. But let’s just say that we have a situation where one in eight Americans is either unemployed or underemployed. There’s still tremendous idle capacity in the labour market. We have a capacity realization rate in industry that’s around 74%. We’re nowhere near the conditions, in terms of the capacity pressures in the economy, that’s going to lead to a sustained increase in inflation. It doesn’t mean that you don’t get some temporary periods of pass through in the goods-producing side from commodities in the weaker dollar, but that’s not lasting inflation.

So which will we get? I suspect both. First off, this summer we will have very low comparisons for inflation if you only look back for 12 months. If we get even a modest recovery in the COVID numbers, we clearly could see some short-term “inflation” in annual data from those weak comparisons. It won’t last. If you look back 24 months (which we never do) you would see inflation still under 2%. And for the record, annualized PCE inflation, the Fed’s favourite measure, is only 1.3% annually today. We have a long way to go to get to 3%.

The debt burden will cap growth enough to keep the inflation mild. It won’t be another 1970s period of sustained inflation. But it might be enough to send gold to record highs. A lot depends on how much inflation the Fed chooses to tolerate. Their recent signals indicate it may be a lot more than we’ve seen in this century. I don’t think they get worked up until inflation is well north of 3% for six months to a year. They have made it clear they want inflation to “average” 2% for a period of time. That means they have to overshoot that target to get that average.

Implications

To get inflation, we have to assume that we have controlled the gripping hand of the coronavirus. Look at what’s happening in Portugal, where B117 recently began taking off.

Source: Our World in Data

This looks almost exactly like the Irish problem. Notice that barely a month ago, Portugal was seeing a steep drop in cases per million, much like the US is today. Then boom!

We really need to avoid such a spike here, first of all to save lives, but also economically. People would stay home and businesses close voluntarily even if governors don’t order it, further devastating our already-weakened economy.

Former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, looking at CDC data, thinks 50% of US coronavirus cases will be the B117 variant by the end of February. If this is the case (and we will know in a few weeks), then it means another very serious spike in cases.

This would leave governors no good choices. Lockdowns which are increasingly shown to be ineffective? No lockdowns and let it run? Nothing but bad options. Fortunately, we are getting better medicines to deal with the disease. The Cleveland Clinic has begun sending nurses to administer IV drugs in patients’ homes, avoiding hospitalization. We will see more such innovation and it will help.

Nevertheless, in a variant-driven spike event, the modestly recovering economy will probably fall back into recession. Recessions are by definition deflationary events.

Obviously we all hope to avoid that, and I think it is quite possible. A few more weeks of solid vaccine progress, warmer weather, continued distancing and other precautions, plus a little luck, might do the trick. But there is no time to waste. I urge everyone: Get vaccinated as soon as it is available to you, and keep avoiding crowds and all the other standard measures. That is the best way you can help the economy, and particularly the small businesses that have been hit so hard. We can get through this but it will require everyone’s cooperation.

Other risks remain, too. Scientists think the current vaccines will still work against the known variants, but that is not yet certain. The South African and Brazilian variants are already in the US. Other variants could appear, too.

It’s also still unclear how long immunity lasts, whether from vaccines or from prior infection. And more than a few people simply don’t want the vaccine, for whatever reason. Reaching “herd immunity” is not a sure thing even when vaccinations crank up.

Then there is the rest of the world. Truly solving this problem requires global herd immunity, which means billions of vaccinations. That part of the battle has barely begun and could take several years.

So the gripping hand, aside from superior strength, has independently moving fingers. We need them all to relax before we can relax. And oddly, that happy outcome might trigger the kind of inflation we’d rather not see. But I don’t expect it this year. And the bigger we build our debt in the US and Europe, the less likely inflation becomes.

If we overcome the virus, the dollar likely continues lower, although the Eurozone is already trying to figure out how to manipulate the euro lower. If we get that spike here? And it shows up in the rest of Europe like it did in Portugal? The dollar bears could get their face ripped off. I think gold does well in any event. Sadly, every prediction and outcome is still in the Gripping Hand. Stay tuned…

Martin Luther Rewired Your Brain

By Joseph Henrich

Your brain has been altered, neurologically re-wired as you acquired a particular skill. This renovation has left you with a specialized area in your left ventral occipital temporal region, shifted facial recognition into your right hemisphere, reduced your inclination toward holistic visual processing, increased your verbal memory, and thickened your corpus callosum, which is the information highway that connects the left and right hemispheres of your brain.

What accounts for these neurological and psychological changes? You are likely highly literate. As you learned to read, probably as a child, your brain reorganized itself to better accommodate your efforts, which had both functional and inadvertent consequences for your mind.

So, to account for these changes to your brain—e.g, your thicker corpus callosum and poorer facial recognition—we need to ask when and why did parents, communities, and governments come to see it as necessary for everyone to learn to read. Here, a puzzle about neuroscience and cognition turns into a historical question.

Of course, writing systems are thousands of years old, found in ancient Sumer, China, and Egypt, but in most literate societies only a small fraction of people ever learned to read, rarely more than 10%. So, when did people decide that everyone should learn to read? Maybe it came with the rapid economic growth of the Nineteenth Century? Or, surely, the intelligentsia of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment, imbued with reason and rationality, figured it out?

No, it was a religious mutation in the Sixteenth Century. After bubbling up periodically in prior centuries, the belief that every person should read and interpret the Bible for themselves began to rapidly diffuse across Europe with the eruption of the Protestant Reformation, marked in 1517 by Martin Luther’s delivery of his famous ninety-five theses. Protestants came to believe that both boys and girls had to study the Bible for themselves to better know their God. In the wake of the spread of Protestantism, the literacy rates in the newly reforming populations in Britain, Sweden, and the Netherlands surged past more cosmopolitan places like Italy and France. Motivated by eternal salvation, parents and leaders made sure the children learned to read.

The sharpest test of this idea comes from work in economics, led by Sascha Becker and Ludger Woessmann. The historical record, including Luther’s own descriptions, suggest that within the German context, Protestantism diffused out from Luther’s base in Wittenberg (Saxony). Using data on literacy and schooling rates in nineteenth-century Prussia, Becker and Woessmann first show that counties with more Protestants (relative to Catholics) had higher rates of both literacy and schooling. So, there’s a correlation. Then, taking advantage of the historical diffusion from Wittenberg, they show that for every 100-km traveled from Wittenberg, the percentage of Protestants in a county dropped by 10%. Then, with a little statistical razzle-dazzle, this patterning allows them to extract the slice of the variation in Protestantism that was, in a sense, caused by the Reformation’s ripples as they spread outward from the epicenter in Wittenberg. Finally, they show that having more Protestants does indeed cause higher rates of literacy and schooling. All-Protestant counties had literacy rates nearly 20 percentage points higher than all-Catholic counties. Subsequent work focusing on the Swiss Reformation, where the epicenters were Zurich and Geneva, reveals strikingly similar patterns.

The Protestant impact on literacy and education can still be observed today in the differential impact of Protestant vs. Catholic missions in Africa and India. In Africa, regions with early Protestant missions at the beginning of the Twentieth Century (now long gone) are associated with literacy rates that are about 16 percentage points higher, on average, than those associated with Catholic missions. In some analyses, Catholics have no impact on literacy at all unless they faced direct competition for souls from Protestant missions. These impacts can also be found in early twentieth-century China.

The Protestant emphasis on Biblical literacy reshaped Catholic practices and inadvertently laid the foundation for modern schooling. Forged in the fires of the Counter-Reformation, the Jesuit Order adopted many Protestant practices, including an emphasis on schooling and worldly skills. Analyses of an indigenous population at the junction of Paraguay, Argentina, and Brazil reveal that the closer a community is to a historical Jesuit mission (which existed from 1609 to 1767), the higher its literacy rate today. By contrast, proximity to one of the Franciscan missions in the same region is unrelated to modern literacy—the Franciscans formed three centuries before the Reformation and hadn’t internalized Protestant values.

The notion of universal, state-funded schooling has its roots in religious ideals. As early as 1524, Martin Luther not only emphasized the need for parents to ensure their children’s literacy but also placed the responsibility for creating schools on secular governments. This religiously inspired drive for public schools helped make Prussia a model for public education, which was later copied by countries like Britain and the U.S.

When the Reformation reached Scotland in 1560, John Knox and his fellow reformers called for free public education for the poor and justified this with the need for everyone to acquire the skills to better know God. Having placed the burden for delivering schooling on the government, the world’s first local school tax was established in 1633 CE and strengthened in 1646 CE. This early experiment in universal education may have midwifed the Scottish Enlightenment, which produced intellectual luminaries ranging from David Hume to Adam Smith. A century later, the early intellectual dominance of this tiny region inspired France’s Voltaire to write, “we look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization.” Voltaire, who grew up in a region controlled by Huguenots (French Calvinists), was educated in Jesuit schools, along with other Enlightenment luminaries like Diderot and Condorcet. Rousseau, for his part, likely learned to read from his Calvinist father in the Protestant city-state of Geneva.

The story of literacy, Luther, and your left ventral occipital temporal region is but one example in a much larger scientific mosaic that is just now coalescing. Our minds, brains, and indeed our biology are, in myriad ways, substantially shaped by the social norms, values, institutions, beliefs, and languages bequeathed to us from prior generations. By setting the incentives and defining the constraints, our culturally-constructed world shape how we think, feel and perceive—they tinker with and calibrate the machinery of our minds.

Joseph Henrich is a Professor and Chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University. This piece draws on the Prelude of Professor Henrich’s latest book, The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West became psychologically peculiar and particularly prosperous (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2020).

Why has the world become so weird?

Why has the world become so weird?

I’m going to do something different this time, which I’ve only done once before, and dedicate the whole newsletter to a single topic. I want to attempt a (partial, first draft) answer to a question we’ve addressed before (e.g. TiB 135) – why has the world become so weird?

The immediate prompt is, of course, WallStreetBets-meets-GameStop-meets-Robinhood, but that’s just the latest installment in a series of increasingly bizarre events that have submerged many of the world’s great institutions since age least 2015-ish. (If you’re looking for commentary on GameStop itself, the best is is inevitably Matt Levine’s – Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri – and if you’re not subscribed to Matt Levine’s newsletter already, well, this is the best tip you’ll get all week).

The short answer to the question is that GameStop is the latest example of variance-amplifying institutions (VAIs) triumphing over variance-dampening institutions (VDIs). These institutions differ in what behaviours they promote and what characteristics they select for. VDIs select for norm adherence, predictability and consistency. They create negative feedback loops; bureaucracy is the canonical example. VAIs select for extremeness, surprise and virality. They create positive feedback loops; the internet is the canonical example.

One way to think about the triumph of modernity is as the gradual reduction in variance across most aspects of our lives. From the Peace of Westphalia to the welfare state, we’ve gradually built institutions that make life more predictable and narrow the range of outcomes to which we’re exposed (with some catastrophic failures along the way, of course). That era is coming to an end.

The Heyday of Variance-Dampening Institutions

For the last few centuries, politics in the West has been increasingly dominated by VDIs. The history of pre-modern politics is largely a history of violence – violence gradually constrained and today (more or less) eliminated. Constitutions and norms that govern, among other things, the transfer of power increase predictability and reduce variance. VDIs have become important at every stage of the political process. For example, until a decade ago the dominant model for understanding US presidential primaries was that “The Party Decides”, not the voters. The odds for wildcard candidates were low.

We saw a similar phenomenon in other areas of life. We talked in TIB 146 about the old world of overlapping corporate board memberships that allowed elite consensus to spread widely and rapidly – a classic VDI. In finance, central banks have played a dampening role for centuries and are now – alongside another VDI, Keynesian fiscal policy – the default instrument for maintaining financial calm in crisis.

Why have VDIs been so successful and persistent? Long time readers will not be surprised that I think part of the answer is that VDIs have built a symbiotic relationship with the most ambitious people in society (see my previous essay on the topic). VDIs have provided a more or less predictable, more or less meritocratic (again, with obvious and tragic exceptions) mechanism for ambitious people to convert talent into power, wealth and status.

One important consequence of this is that for many decades, most ambitious people have not been doing catastrophically destabilising things. You might not like McKinsey, Goldman Sachs, Google, et al, but hierarchical institutions are an ambition shock absorber. The people competing to get to the top of each are (generally) following rules and channeling their ambition into non-violent, non-destructive activity – a happy anomaly in historical terms. This makes for fairly coherent, homogeneous elites (which again you might dislike) who are committed to societal stability.

The internet and the new era of variance

The internet changes all this. It is the ultimate variance-amplifying institution. It inverts many of the core features of the VDIs that preceded it. Above all, it is permissionless and uncapped. On the internet anyone can do anything and, in theory, can reach any scale. Unlike the hierarchical institutions we have become used to, the internet does not select for the least disruptive or the most conforming, but for the most meme-able, share-able and bandwagon-able. And the internet has spawned a legion of offspring VAIs: Reddit, Robinhood, Twitter, and many more.

This changes the elites we get and how they behave. As I’ve argued before, startups – archetypal VAIs – are an increasingly attractive path for the most ambitious, precisely because they allow for extreme outcomes on impatient timelines. This creates a subset of elites who owe little to conformity and norm adherence. In general, the winners of internet-scale contests look and behave nothing like the winners of hierarchical contests – compare Elon Musk to Pierpont Morgan; Donald Trump to… any pre-Trump presidential candidate. This, in turn, accelerates the feedback loop.

More importantly, VAIs allow everyone to a shot at greatness – or, at least, a day in the Twitter trends. Just because you can’t climb an institutional hierarchy doesn’t mean you can’t “meme a president into existence” or bankrupt Wall Street. Of course, it is truly an uncapped game, in both directions, which means that in a VAI some days you’re u/DeepFuckingValue and some days, tragically, you’re Alex Kearns. It may be that r/wallstreetbets contains more college graduates than “deplorables”, but in a world of intra-elite competition and predatory precarity, even the upper middle class has the incentive to roll the dice.

The variance genie can’t easily be put back in the bottle, at least not without severe repression. There is no “pre-2016” world to return to. A free internet entails a world more variance and more tail risk. We must learn to live with it. We learned to live with the printing press too – an undoubted boon for the world (though not before it had helped wreak destruction across a continent). The solution must be countervailing institutions – new VDIs that can stabilise outcomes without a kill switch. We need the Peace of Westphalia of the internet age. Let’s hope it doesn’t take us quite so long.

Q&A: 2021 and beyond – looking forward to the new roaring 20s

Investec sponsored panel discussion

We’ve once again asked our panel of Investec Wealth & Investment strategists and other investment brains (from as far afield as Cape Town, Johannesburg and London) to answer a list of questions about the outlook for the year. Once again, there’s a broad range of views and angles about what are likely to be the key investment talking points for the coming year.

Our panel is made up of the following:

- Professor Brian Kantor (economist and strategist)

- Barry Shamley (portfolio manager and head of the ESG Committee)

- Bradley Seaward (portfolio manager)

- Chris Holdsworth (chief investment strategist)

- John Wyn-Evans (head of investment strategy, Investec Wealth & Investment UK)

- Neil Urmson (wealth manager)

- Richard Cardo (portfolio manager responsible for the Global Leaders portfolio)

- Zenkosi Dyomfana (portfolio management assistant)

Key:

BK = Brian Kantor

BS = Barry Shamley

BSE = Bradley Seaward

CH = Chris Holdsworth

JWE = John Wyn-Evans

NU = Neil Urmson

RC = Richard Cardo

ZD = Zenkosi Dyomfana

Q&A January 2021

Covid-19 remains the key topic for the year ahead and will likely remain so for some time. With vaccines being rolled out, what is your sense of the trajectory of the post-pandemic recovery and the timing of a return to “normal”?

CH: I suspect it will be very different for developed and emerging markets. Wealthy countries with competent governments will see a quick roll out of the vaccine, while poor countries and countries with incapable states may well see another round of lockdowns, as the only way to control the virus, before the virus is a thing of the past. The US is already rolling out over one million vaccinations a day and it should be just a matter of months before herd immunity is achieved both there and in the UK.

BK: Normal will be when herd immunity is attained, with the aid of vaccines. In the US I see this happening by the end of Q3 2021, in Europe a little later and in the UK somewhat earlier. In SA, not before Q1 2022.

JWE: It will happen gradually through Q2/Q3 2021 in those countries that have vaccine supplies. Normal will still include various restraints – eg masks/vaccine certificates for travel and mass gatherings.

ZD: We are witnessing, and will for some time, a multi-speed recovery, sector by sector, with those that were allowed to operate having some advantage, followed by those that opened in the early easing of restrictions. Medium- and larger-sized businesses have fared better, aided by their reserves and capacity. We are also beginning to witness divergent economic recoveries, with China rebounding well-above expectations, while the GDP growth consensus expectations is optimistic for the US and pessimistic for UK, France and SA.

The impact of the lockdowns is likely to have a long tail i.e., the economic consequences of the pandemic are still to be felt and fully transmitted through the system, as seen in increases in retrenchments

The best case is that 2021 is a year of structural adjustment to the new normal, and the new normal is something we will see in the first half of 2022 where we will have a trajectory change across businesses. The key risk to this narrative is the pace of vaccine rollouts.

RC: We are entering a new economic upswing. Economic growth in most developed markets should return to pre-Covid-19 GDP paths during the second quarter of 2021, given that developed markets are generally ahead in the roll-out of vaccines. Unfortunately, many emerging markets are behind the curve in vaccine procurement and distribution, so may lag by six to 12 months in their economic recovery – though China is the notable exception. That said, a rising tide lifts all ships so the expectation is that emerging markets will catch-up aided by buoyant commodity prices and demand and a gradually weakening dollar.

BSE: Similar to the K-shaped recovery in companies, I see the same in economies around the globe. Some economies will continue to thrive, while others will take a while to bottom.

BS: Normal doesn’t seem like its returning any time soon, but I suppose that’s what it always feels like in the midst of a crisis. We have passed peak uncertainty, but it will be some time until we can step back and count the cost to society. Central banks have intervened and mitigated much of the economic damage, but unfortunately there is only so much they can do. Many lives and valuable businesses have been destroyed. The initial economic bounceback has been rapid but for those starting again it will take some time.

NU: Developed markets should be back to normal by the end of the year, if not earlier. For emerging markets, it’ll be end of year for some and then end of Q1 next year.

The pandemic has changed our lives in many ways. As we slowly get back to a normal way of life, which of these changes will become permanent and in which ways will we go back to the old ways of doing things? What are the implications for investors?

CH: Working from home is likely to stick, at least in part. I’m sure there will be much less business travel going forward too. Inadvertently, this may see a rise in productivity with less time wasted in traffic and waiting in airport lounges. A rise in productivity should see higher wages, at least for those who have retained their jobs.

Manufacturers have been forced to find ways to operate with reduced headcounts and some of this may well stick too. Many restaurants will not survive and many of the layoffs at the low end of the income spectrum may prove to be permanent.

The result of both of these trends is a rise in income inequality, something that is deeply unpopular even now. It may well be the case that Covid has accelerated the argument for wealth taxes and basic income grants.

Working from home may mean that corporates revisit the need for large scale head offices. Office rentals will likely take a long time to recover, while home construction takes off to build home offices (I’m not sure what the long term health effects will be from eating lunch at home vs at the canteen, but at least it will be a test of self-discipline).

RC: The health pandemic has pulled forward and accelerated our adoption of online technology, more flexible and remote working, and advancements and improvements in health and environmental safety standards. Technology enablers, internet platforms, cloud businesses and subscription services have benefitted substantially and will continue to do so. e-commerce penetration in the US has doubled since the end of 2019 and is now at a level of 33%, while the level of digitisation of businesses is up 60%, to a level of 55%, over that same time-period. Those companies that cannot embrace and lead in in e-commerce, the digital transformation of business, data handling, workflow automation, security of supply chain, wellness and hygiene, adopting a greater focus on the social contract and being more purposeful, will increasingly be left behind.

But humans are inherently social beings and as cocooning trends and mobility restrictions ease, we expect currently anxious consumers to embrace human movement and spend once again on many traditional ‘old normal’ experiences and goods. Notwithstanding the level of job losses and business failures brought on by the pandemic, US household incomes have increased by around a net $650bn, while US households’ net worth has increased by more than $5 trillion, and US households currently have around $1.5bn in excess savings to date. This means that once confidence returns, which it will, there should be a lot of pent-up demand and spend.

BK: Working from home is an option for more people. And the quality of the video links and other connections will improve, helping to develop the virtual office. Productivity of home work is still to be measured. The jury will be out for some time. Working together, as before, is necessary when it comes to collaboration, innovation and supervision. Working from home may not deliver as much as face to face. But much experimentation will be made. Trade-offs will be made when it comes to transport costs, office space and take home pay. The choices for workers and hirers are wider than before. We should be in no rush to discover what works best. Trial and error as always will decide the outcomes. No cookie cutter solutions – only gradual responses to choices exercised will be called for. The market processes will adapt, as always, and governments will be wise not to plan too narrowly or too far ahead. Public transport (roads, railways etc) may become less important and require less capital expenditure in the future.

ZD: The pandemic accelerated themes that were underway and one of those is the adoption of digitisation. Businesses have realised that certain functions, especially those that require fewer human interactions such as call centre operations, can be run remotely and this will eke out some cost efficiencies and improve profitability. Covid has given a boost to the willingness to try out online platforms for the purchase of products and services, and clear benefits of this are convenience and time saved. Going digital is now a fact of life (in the US there’s been an increase of 80% in first time users), so there is no getting around it anymore. As such, Covid has flushed out some of the bad business models and enabled the good ones. Capital will be looking for and rewarding good businesses that are agile and adaptable, with strong balance sheets and quality management teams.

BS: I think people have realised that they cannot take anything for granted. I think lives will be lived with a higher degree of caution and a greater appreciation for normality. Investors have endured volatility but have been rewarded for not panicking. I expect global central banks to continue to be very supportive as we manage our way out of this devastating crisis.

JWE: I think business travel will probably be the biggest victim. I see more working from home, but overall no real implications for investors outside of regular stock/sector selection.

BSE: Humans are social beings, so the need to congregate and meet in person remains a theme which I believe will stick. Relationships are truly forged face to face, however maintenance of those relationships can be done online. These allow for a couple of themes – less business travel, less need for business accommodation, which makes room for more leisure travel – a remote worker can operate from anywhere. So I believe that companies which cater to business travel will need to revisit their business models. Companies in the client service space will need to be more flexible with their staff. Investors will have to look out for companies which are ahead of the pack in these themes.

NU: I think the working environment will change somewhat but not as much as some people think. The adoption of technology has definitely accelerated. However, investors should continue to apply the same time-tested investing principles.

With Joe Biden in the White House and a Democrat “light blue” sweep in Congress, what does this mean for US economic policy? Will this be good for global growth?

CH: Biden’s policy agenda is likely to see more stimulus now and more taxes later. In aggregate this is likely to be positive for growth over the short term at least. However, assumptions of an easing of tensions with China may well be premature. At some point the US and its allies are likely to bump heads with China again, given China’s rising influence and competition with developed markets.

BK: I see more spending, more being given away, bigger deficits, bigger government and maybe higher taxes. I also see more hostile-to-business regulation. The Democrats will be friendlier to unions and the exercise of their protections. All of this is good for growth for now, but a bigger, more intrusive government is not helpful for growth in the long term and will become the case for voting out the Democrats.

JWE: I see more stimulus, higher taxes and wealth redistribution. On balance, I’m generally positive.

ZD: The Democrat victory in November 2020 is positive for global growth and equities. In the wake of the carnage from the pandemic, getting the virus under control, rolling out the $1.9 trillion fiscal stimulus package, business recovery and job growth will be prioritised by the new administration and this will increase the global economy. Corporate tax reversal could dampen economic growth in the US, but to a less degree. Other policy proposals including infrastructure spending, softening tariff rhetoric and higher wages should be net positive and largely offset the tax headwind.

The largest headwind for global growth in 2019 was tariffs. President Biden has emphasised reducing trade barriers and wants to build an international coalition against China as opposed to unilateral tariffs. Further, with the status quo re-established and the virus under control, we will likely see lower equity volatility and risk premia, and markets trending higher.

BS: US economic policy will be impacted far more by the aftershocks of the virus. What Biden and the Democrats will provide is stability and certainty, which has been sorely lacking under Trump. This should be beneficial for global growth as investors can invest with a greater degree of confidence.

RC: I would expect some immediate easing in global trade tensions and a rollback of the existing Trump tariffs and isolationist policies, which will be good for global economic growth and a tailwind for US corporate profits. The other focus near-term will be on increased fiscal stimulus, government spending and pro capital expenditure policies, which are more politically palatable given a health pandemic, and will support global economic growth. Democrat economic policies should benefit emerging market economic growth and help to keep the US dollar on the back foot, which in turn would be a significant boon for multinational (global) company earnings. The fear is that Democrat tax reform, the hiking of taxes and tightening regulation – particularly in the energy, healthcare, banking and technology sectors – will outweigh the abovementioned positive policies and prove to be a net material drag on corporate profits and economic growth. But that has become less likely a concern in the near term given the ‘light’ sweep: there is still a fairly even balance of powers in the legislative corridors, and likely easier wins to be made elsewhere as mentioned above. A Democrat sweep is typically good for the US stock market, which has on average generated returns of more than 13% over the subsequent 12 months.

Nonetheless the US remains a divided society. How will these divisions impact its growth and policy in the coming years?

CH: The Republicans have little ability to obstruct the Biden agenda, aside from appealing to more conservative Democrat representatives. This by itself will force the right further to the centre, which may well see further divisions in the right. In short, the Democrats will probably have it their way for at least two years.

BK: All societies are divided in opinion. Trump was an extraordinarily divisive personality. The progressive establishment hated him. The Republicans will need to come up with leaders who can also appeal to the Trump heartland and pursue his anti-woke agenda. The promise to drain the swamp will have much support – after the Democrats have revealed their colours (or is it colors?).

JWE: Biden’s policy will try to bridge divisions. However, I should point out that the US is probably more unified in the “centre” than we give it credit for, although it’s the “wings” who get the headlines.

ZD: Biden talked about unity in the lead-up to his inauguration and in his presidential speech, stating that he will be a president for those that voted for him and those that did not vote for him. One of the tools his administration will lean towards to achieve this will be addressing inequality and racial economic injustice through minimum wage and social welfare budgets. This will likely result in increased consumer demand and economic growth. However, there is a regulation risk: the new administration could try to level the playing field when it comes to the market incumbents, through anti-trust laws and higher taxes. This could have an offsetting impact on the economy.

BS: I don’t believe that the US is as divided as is portrayed by the media. There are always those on the fringe who make a big noise and grab a lot of media attention, but ultimately there is the majority that just want to get on with their lives, make a living and interact with their fellow countrymen in an honest and empathetic manner.

NU: It all depends on numerous issues but at the margin the divisions in the US are a negative and have the potential to become really negative. I see inflation (through the policies to be adopted) as a definite possible consequence.

What are the implications on geopolitics of a Biden presidency? What does this mean for global trade policy, human rights and the environment?

CH: Positive for all three. The US is re-joining the Paris climate accord and we can expect an easing of trade tensions. However, Biden may well still push for an ‘buy American’ policy and US carbon emissions in 2018 were already 10% below 2005 levels. In effect, the optics may change but the final outcome may not be materially different when it comes to trade policy and carbon emissions.

BK: There’s more scope for flawed global institutions. The Democrats will also find out how little love there is for Americans. I see little change in the outcomes but I also see more of a virtue-signalling environment in which bureaucrats will meet with less resistance. The anti-woke Trump was an aberration. Will we see his populist type again? There are popular populists elsewhere – Hungary and Poland spring to mind. Or will we see him again?

JWE: Trade policy in general will be more helpful. However he could be more hawkish on human rights, which suggests continued pressure on China

ZD: Biden has signalled his administration will ease trade tensions against China and this is good for international trade. However, he has made it clear that he will be firm with China if it does not play nice, and his administration is committed to take on China’s abusive, unfair and illegal practices.

Climate change is one of the biggest global risks and Biden understands this. He has placed climate change at the forefront of becoming his signature policy and has already re-joined the Paris accord, and halted the withdrawal from the World Health Organisation. The US’s leadership in climate change is important in fighting it. The regulation in clean energy, electric vehicles etc. is about leading for the future as opposed to fighting to preserve a fossil fuel-based economy, and we have seen demand for that. This green shift is not likely to curtail growth but improve it, as new investments are made in this space.

NU: All good when compared to Trump – the question is, will it be as good as expectations?

What are your views on China’s positioning in all of this? How well is it placed in achieving its goals after the pandemic?

CH: China had a good crisis. Its economy now accounts for 15% of global GDP, two years ahead of forecast. Chinese GDP is due to overtake the US in 2028. However, China faces two long-term threats to prosperity – competition with established developed markets and demographics. Given the aging population in China, and the persistently declining working age population, it may well be the case that China gets old before it gets rich. In addition, rising competition in high-end manufacturing and intellectual property may well see an increasingly hostile relationship with the US and Europe.

BK: The Chinese are more respected but less loved. But they come with money and are a larger threat to the post-enlightenment societies that are increasingly ignorant of the reasons for their material welfare and political freedoms – freedoms that China does not respect. China offers a totalitarian and nationalist alternative. Free countries will need to keep up their guard and unfree countries are less likely to become free with Chinese assistance.

JWE: China is in decent shape to follow its path. Betting against it has not worked in the past and I’m not sure it will work now either.

ZD: China’s economy is recovering well. It’s ahead of all other economies and appears to be getting closer to achieving its ambitions of being the biggest and most powerful economy. A strong Chinese economy is good for commodities, emerging market economies and markets overall.