The Investor December 2015

We at RCIS would like to wish all our readers a blessed Christmas and a prosperous New Year. Please note that our offices will be closed from noon on December 24 to January 4

The all new ShareFinder 6 is here for you to try on Jan 10th!

Offering you gift overseas portfolios!

by Richard Cluver

After nearly four years of research and development, the ShareFinder 6 is finally complete and ready for final beta testing in your hands ahead of a general release in January.

Unlike all its predecessors, the latest programme is hosted in “the Cloud” which means you will no longer be desk-bound. You will instead be able to access your portfolio from anywhere using a laptop, tablet or smart phone and it will always be up to date offering you a full analysis of the health of portfolios of shares listed in the US, Britain and Australia as well as South Africa. You will, furthermore, be able to act immediately on buy/sell recommendations provided by the programme because it links automatically to the biggest stockbroking firm in the world; Saxo Capital.

After all the hype that has preceded the launch of the latest ShareFinder programme, users might be surprised to find that it looks and feels exactly like the old ShareFinder 5, but that has been done deliberately to ensure that current users of our software will be able to make the transition with ease. However, though it looks the same, under the bonnet it is a much more powerful vehicle offering far greater accuracy of analysis.

Most importantly for South African users faced with the threat of a steadily collapsing Rand, ShareFinder 6 offers access to the New York Stock Exchange, The Nasdaq, the London Stock Exchange, and the Sydney Stock Exchange. And during the course of 2016 we will be adding all the remaining major world stock exchanges. Using the same “Portfolio Builder” facility that programme users have become used to in ShareFinder 5, you will be able to choose the top-performing shares from all the major countries of the world in order to create portfolios largely insulated from economic swings which have made single-country portfolios so hazardous in recent years.

But the best feature of all with the new programme is its cloud computing facility. No longer will you have to go through the daily process of downloading market data before you can perform your daily portfolio examination. Updates will be performed automatically within our central computers located strategically all over the world. Accordingly, programme-users will no longer have to contend with database corruptions and software reinstallations.

Furthermore you will no longer need to buy the programme. Access to the SF6 is via a low monthly subscription which will ideally be charged month by month to your credit card.

We are now releasing the final programme “Beta” ahead of a full launch in January and those existing SF5 users who would like to participate in this final test should contact support@rcis.co.za so that we can link you up.

The other good news is that we are endeavouring to hold down costs. Recognising that we have ShareFinder users all over the world we have opted to price our software in US Dollars but, as an example, South African subscribers will pay R300 a month which is less than the present annual costs of the data used by the old ShareFinder 5. That will give you access to any one market of your choice and for just another R50 a month each you will be able to add as many other markets as you choose. Existing users will be credited pro rata for any payments in advance they might have prepaid for supplemental data from RCIS in respect of the old SF5. US users will pay $49 a month and $10 per additional market. British Users will pay 35 pound a month and 10 pounds per additional market.

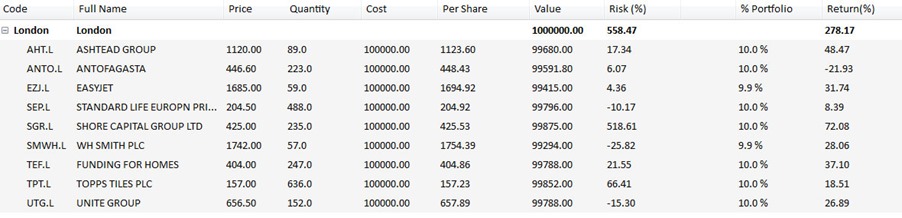

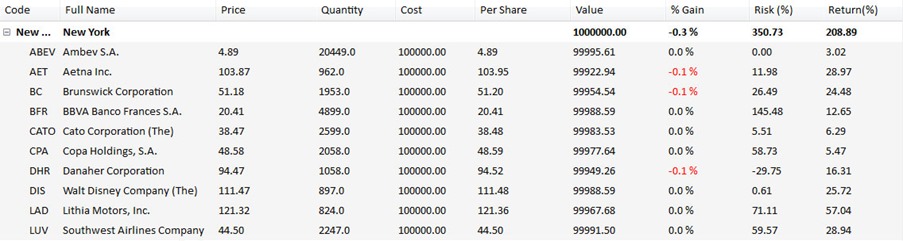

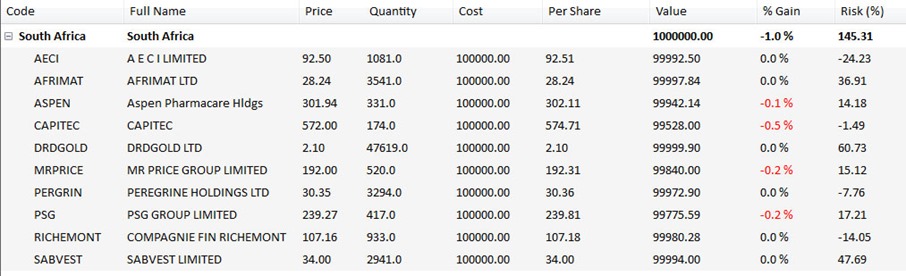

Here, as a festive season gift to you are three portfolios selected by the new SF6 representing ten safe high-growth shares on the London, New York and Johannesburg stock exchanges. Of course, recognising that there is always a trade-off between risk and return, the new SF6 will tailor portfolios specifically to your own ability to tolerate risk and your need for either steady dividend income growth or rapid capital growth.

The three portfolios which appear below are constructed for people who can tolerate a reasonably high degree of risk in the interests of growing their money as fast as possible. Here it is important for our South African and Developing World readers to note that their currencies have been declining in value by an average of 19.4 percent compound over the past five years which makes the London portfolio Total Return of 278 percent and the New York portfolio total return of 209 percent infinitely more attractive than the 145 percent the JSE offers. Even if you believe that the Jacob Zuma administration is capable of improving in the long term, these figures represent an overwhelming case for investing as much abroad as you can afford. Do note, however, that the South African portfolio offers a significantly lower price volatility rate as denoted by its aggregate “Risk”. What this latter observation means is that when buying into overseas markets you need to pay far greater attention to buying into market cycles; by using tools that SF6 offers to time your purchasing for optimum value.

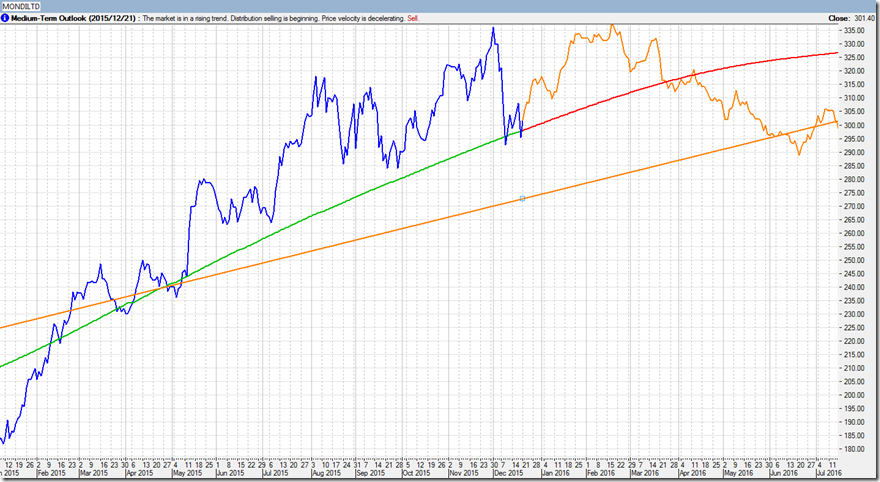

Be advised, however, that ShareFinder users never simply buy a portfolio recommendation without also employing the programme’s artificial intelligence system which projects forward likely price movements with better than 80 percent accuracy. Thus, for example, the projection below for Mondi shares suggests that the optimum purchase date is likely to be in mid-June next year:

Do we thank the informal (unrecorded) sector?

By Brian Kantor

Chief Economist and Strategist, Investec Wealth and Investment

We have received some useful information about the state of the SA economy at the end of November 2015. New motor vehicle sales and cash in circulation at month end November present something of a mixed picture. We examine both below and combine them to update our Hard Number Index (HNI) of the current state of the SA economy.

Vehicle volumes in November came in marginally ahead of sales a year before and on a seasonally adjusted basis were also slightly ahead of sales in October 2015. But the sales cycle, when seasonally adjusted and smoothed, continues to point lower, albeit only very gradually so.

The local industry is delivering new vehicles at an annual rate of about 600,000 units and the time series forecast indicates that this rate of sales may well be maintained to the end of 2016. Such an outcome would be regarded as highly satisfactory when compared to peak sales of about 700,000 units back in 2006. (See below) For the manufacturing arm of the SA motor industry, exports that are running at an impressive, about half the rate of domestic sales, are a further assist to activity levels. This series may be regarded as broadly representative of demand for durable goods and equipment.

New Unit Vehicle Sales in South Africa

Source; Naamsa, I-net Bridge and Investec Wealth and Investment.

The demand for and supply of cash in November by contrast has been growing very strongly. By a 10.6% p.a or 5.7% p.a rate when adjusted for headline inflation of 4.6%. This represents very strong growth in the demand for cash- to spend presumably. Though as may also be seen the cash cycle may have peaked.

The extra demands for cash presumably come mostly from economic actors outside the formal sector. The formal sector has very convenient electronic transfer facilities as alternatives to transferring cash. Electronic fund transfers have increased from a value of R4,919b in 2009, that is nearly 5 trillion, to R8.4t in 2014 or at a compound average rate of 8.9% p.a over the six years. Over the same period credit card transaction increased from R142,198b in 2009 to R258.6 by 2014 or by a compound average rate of 9.9% p.a while the use of cheques declined from a value of over R1.1t in 2009 to a mere R243b by 2014.

The supply of notes issued by the Reserve bank has grown from R75.2b in November 2009 to R134.7b in November 2015, that is at a compound average rate of 9.7% p.a. That is the demand for and supply of old fashioned cash has grown in line with the growth in electronic alternatives. Clearly there is a great deal of economic activity in South Africa that escapes electronic action or surveillance. We show the respective nominal and real note cycles below. Both show a strong acceleration in 2015.

The Cash Cycles- annual growth in the note issue.

Source; SA Reserve Bank; I-net Bridge and Investec Wealth and Investment.

The note issue cycle and the retail sales cycle in money of the day are closely related as we show below. The advantage of observing the note issue is that it is a much more up to date statistic than is the estimate of retail sales, the most recent being for September 2009. The strength in the note issue in November 2015 bodes rather well for retail sales in December and perhaps especially so for sales made outside the electronic payments system.

The cash and retail cycles. Current prices

Source; SA Reserve Bank; I-net Bridge and Investec Wealth and Investment.

When we combine the vehicle cycle with the cash cycle we derive our Hard Number Index (HNI) of economic activity in SA. As may be seen the HNI indicates that the SA economy continues to maintain its current pedestrian pace, helped by strength in the note issue and not harmed too severely by the downturn in unit vehicle sales.

As indicated 2016 seems to offer a similar outcome. The HNI is compared to the Reserve Bank Business Cycle Indicator that has been updated only to August 2015. The HNI can be regarded as a helpful leading indicator for the SA economy-more helpful than the Reserve Bank’s own Leading Economic Indicator that consistently has been pointing to a slow down since 2009 – a leading indicator belied by the upward slope of the Business Cycle itself- and the HNI. ( See below)

S.A. Business Cycle Indicators (2010=100)

Source; SA Reserve Bank; I-net Bridge and Investec Wealth and Investment.

The slow pace of economic growth in SA is partly attributable to the dictates of the global business cycle. The weak state of global commodity and emerging markets remains a drag on the SA economy. Any business cycle recovery in SA will have to come from a revival in emerging market economies linked to a pick-up in metal and mineral prices that will be accompanied by a stronger rand and less inflation and perhaps lower interest rates. This prospect now appears remote. Though a mixture of stronger growth in the US and Europe with less fear about the Chinese economy would be very helpful to this end. South Africa could help itself with growth improving, market friendly, structural reforms. This prospect unfortunately appears as remote as the recovery in global metal markets.

Thought from across the Atlantic

by John Mauldin

Today’s Outside the Box is from my friend Danielle DiMartino Booth, who used to work at the Dallas Fed for Richard Fisher. She has gone out on her own and has begun to write occasional pieces that seem hit my inbox at least weekly. The cover a wide range of topics, but many of them deal with the Fed.

What if it really is all about reinvestment and not one teensy quarter-point rate hike? Over the next three years, some $1.1 trillion in Treasuries could roll off the Fed’s balance sheet if reinvestments were to cease. Tack on the potential for mortgage backed securities (MBS) to prepay and/or mature and you’re contemplating a figure that approaches $2 trillion.

Make no mistake, shrinkage of the Fed’s balance sheet to half its current size is much more feared by market participants than a slight tick-up in interest rates. Taking the step to not reinvest would increase the supply of Treasuries and MBS available to investors and reduce the Fed’s support of the economy. The higher the supply on the market, the lower the price and hence, higher the yield, which moves opposite price.

I should note that she predicted the Fed would expand its overnight reverse repo program to the tune of $2 trillion, and the Fed has done just that. That should be enough to cover most contingencies for the next few weeks; and, as Danielle explains, that move has a great deal more impact on the markets and your returns than an itsy-bitsy 25-basis-point increase in short-term rates.

Danielle weaves a story about what will really happen over the coming year, based on her knowledge of what Fed members are likely to do and what the markets may force them to do. If you are not much interested in Federal Reserve policy and how it is created, her writings might seem to take you deep into the weeds; but given the importance of Fed policy to the markets, maybe this one time you should pay attention to what goes on behind the curtain. I think this makes a great and timely Outside the Box.

What if Mario Draghi really did whip out a bazooka?

On December 3rd, the stock market pitched a fit reacting to what it perceived to be insufficient stimulus on the part of the European Central Bank (ECB). The market had wanted “Super Mario,” as investors have lovingly nick-named the ECB president, to take two measures.

The first would have expanded the quantitative easing (QE) program, increasing the amount of securities the ECB is committed to purchase. The second would have cut already negative deposit rates by -0.15%; Draghi only delivered -0.1% (negative rates penalise banks for holding excess cash at the EBC when they could lend it out to spur economic growth.)

Borrowing a page out of New York Federal Reserve President Bill Dudley’s battle plan, Draghi did manage to push through a much more forward-looking program – reinvestment of any proceeds that result from securities maturing on its balance sheet. Bratty fast-money, instant gratification investors dismissed the move.

Draghi, though, never looked more the cat that ate the canary than he did the next day in New York. He vociferously reiterated his commitment to do whatever it takes to get inflation to the ECB target, as long as that might take. If QE wars need be fought long into the future, reinvestment will strategically position Draghi on the central banking battlefield.

Back at home, many market watchers are scratching their heads as to why the Fed would be raising rates at this juncture. Financial conditions have tightened, not eased, since the Fed pushed the hold button at its September meeting.

What if it really is all about reinvestment and not one teensy quarter-point rate hike? Over the next three years, some $1.1 trillion in Treasuries could roll off the Fed’s balance sheet if reinvestments were to cease. Tack on the potential for mortgage backed securities (MBS) to prepay and/or mature and you’re contemplating a figure that approaches $2 trillion.

Make no mistake, shrinkage of the Fed’s balance sheet to half its current size is much more feared by market participants than a slight tick-up in interest rates. Taking the step to not reinvest would increase the supply of Treasuries and MBS available to investors and reduce the Fed’s support of the economy. The higher the supply on the market, the lower the price and hence, higher the yield, which moves opposite price.

“It seems to me you’d like to have a little room before you start ending the reinvestment… (which) is a tightening of monetary policy.” So said Dudley on June 5th to a group of reporters. He went on to define how big the ‘room’ needs to be a “reasonable level.”

“By how far that is – you know, if it’s 1 percent or 1.5 percent – I haven’t reached any definitive conclusion.”

At the risk of allowing the appearance of decision-making to occur in unilateral fashion on Liberty Street, Fed Chair Janet Yellen made clear to reporters that the entire Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) was tasked with determining the future size of the balance sheet.

In a June 17 Q&A session that followed the FOMC meeting, Yellen assured the public that, “President Dudley was expressing his own personal point of view, but this is a matter that the committee has not yet decided and I cannot provide any further detail.”

But what if there’s more than one way to skin the reinvestment cat?

The interest rate markets that determine the cost at which banks lend to one another is notoriously illiquid at the end of calendar quarters and years. The Fed knows this. That makes the insistence on raising interest rates this month all the more intriguing given the pressures emanating from the corporate bond market.

As watching-paint-dry boring as the mechanics surrounding the actual rate hike are, a rudimentary understanding is crucial to grasping the tumultuous nature of the deliberations among FOMC voting members. (That was a preamble to implore the reading of the next few paragraphs.)

The overnight fed funds rate market, which the Fed employed to embark on its last rate-hiking cycle, is a shadow of its former self in terms of trading volumes. We’re talking about $50 billion a day compared to today’s theoretical $2 trillion in institutional cash dehydrating on bank balance sheets parched for safe positive yields.

It’s a complete unknown what portion of this $2 trillion would rush off bank balance sheets into money market funds. That said, it’s a slam-dunk assumption that the demand for higher yields is ubiquitous among those making south of nothing on their cash.

Planning for a complete unknown dictates that the Fed be flexible in trying to minimize overnight rate market upheaval. Funny thing – policymakers have a tool that can maximize a smooth transition called the reverse repurchase ‘repo’ (RRP) facility.

In the post-zero interest rate world, which celebrates its seven-year anniversary the day the Fed is expected to raise rates, repo markets determine overnight rates. Banks and other financial institutions swap collateral in the form of U.S. Treasuries, MBS and corporate debt to other investors for cash. In that these are overnight trades to facilitate the shortest-term funding needs, the bank buys back the securities the next day.

A bank in the above example that’s selling securities overnight, with the understanding they’ll buy them back the next day, is entering into the repurchase agreement. The party on the other side of the transaction, which buys the securities overnight agreeing to sell it back the next day, has entered into a reverse repurchase agreement.

Mitigating any disruptions in this market is key to a successful initial rise in interest rates. That’s saying something when the size of the collateral market has already shrunk from $10 trillion in 2007 to $6 trillion today. A rate hike, in its simplest form, involves reducing the liquidity in the system from this $6 trillion starting point. It follows that the Fed can use its RRP to absorb liquidity using money market funds as the conduit.

The problem is the RRP is currently capped at $300 billion per day, a fraction of the potential demand for the discernible yield money market funds will presumably be able to offer in a positive rate environment.

Of course, the Fed could satisfy the need to provide the market with collateral by selling Treasuries, but again this shrinks the balance sheet.

What of the elegant solution cleverly proposed by Dudley, you ask? The answer: Temporarily lift the cap off the RRP to act in the markets’ best interest. In the blink of an eye, the money market fund industry will be completely dependent upon the RRP as a one-stop shop for overnight collateral. In a world bereft of collateral sourcing to begin with, how could such a dependency imply anything “temporary”?

The short answer is it won’t. The long-term devilishly detailed answer: Yes, the Fed uncapping the RRP would succeed in tightening financial conditions by absorbing monies from the money market funds that will be flooded with deposits. But this manoeuvre will not release the collateral from the Fed’s balance sheet. The size of the mammoth balance sheet would thus be largely held intact.

Perhaps this is why we’ve been hearing dissentious grumblings from unusual suspects such as Fed Board governors Lael Brainard and Daniel Tarullo. Monetary policy is effectively being determined mechanistically at an illiquid time of the year notorious for mechanical dysfunction. Policymaking by proxy has to bristle even the loyalist of consensus builders.

Recall that there have been only four dissents on the part of Fed governors over the past 20 years (Federal Reserve district president dissents are relatively-speaking a common occurrence). If dissent weren’t a clear and present danger, why would Yellen warn Congress she’s prepared to push forward with a rate hike in spite of potential dissents? The chair could easily have been referring to mutinous governors.

Since the creation of the RRP, policymakers have gone to great pains to reassure the public they have the political will to shrink the facility when the time comes. That would be quite the acrobatic act if the money market fund industry becomes reliant on the RRP for daily functionality.

Conveniently, with markets pricing in all of two additional rate hikes in 2016, we’ll never get to Dudley’s 1 to 1.5-percent overnight rate that justifies shrinking the balance sheet.

Will policymakers have the luxury of time to raise interest rates enough to combat the next recession? Looking 12 months out, it’s much more likely that the business cycle will have turned. As the Wall Street Journal has pointed out, at 78 months, the current expansion is longer than 29 of the 33 dating back to 1854.

There’s no doubt the Fed’s first rate hike in nearly a decade is an awakening. The open-ended question is the true motivating factor. Perhaps investors should cue off Draghi’s recent success in securing ECB balance sheet reinvestment and connect the dots from there.

Tags: investing, the investor